“Material culture” is the sociological/anthropological term for the things and places associated with a group’s identity and culture. This includes dwellings, places of ceremonial gathering, workplaces, artwork, manufactured goods, food, books, walking paths, neighborhoods – basically everything you can see and touch in a physical location, including the location itself. By studying the physical elements a society uses, you can learn a great deal about the people in that society, because their material culture is closely related to their “nonmaterial culture”: the habits, beliefs, codes of ethics, and ideas they hold. And that’s because physical things are also symbols that represent different aspects of non-material culture.

As individuals, we often ascribe meaning to the things we own that go far beyond their utility and function. For instance, in my desk drawer is a Leatherman PST multitool that my late father-in-law gave me in 1984. The PST is the first multitool made by Leatherman. Compared to the highly evolved multitools of today, my Leatherman is clunky, heavy, and awkward to use. The blade doesn’t lock, making it dangerous, and I need both hands to open it. Production on the PST ended in 2004, when it was replaced by more evolved models. But instead of upgrading to the latest Leatherman tool, which is made of lightweight titanium and has a blade you can open with one hand, I treasure my PST. Every time I use it, I remember the times I spent with my father-in-law. There’s no way I’d part with this tool.

You, too, undoubtedly own things that have little or no intrinsic value, but which you nonetheless consider priceless. It’s part of being human. The pioneering psychologist Jean Piaget discovered that babies felt a sense of ownership over objects and would go into a “violent rage” when one of them was taken away. The term for this kind of behavior is called the “endowment effect.” In a 2008 experiment led by Princeton scientist Daniel Kahneman, volunteers were given a coffee mug. Once they had the mug in their possession, they were offered to trade it for a bar of chocolate. Most turned down the offer, preferring to keep the mug. A separate group of volunteers was given the chocolate bar first, then asked if they would be willing to part with it for the mug. Again, the majority of volunteers told the psychologists, “no deal.” Our possessions, it seems, become part of us.

You, too, undoubtedly own things that have little or no intrinsic value, but which you nonetheless consider priceless. It’s part of being human. The pioneering psychologist Jean Piaget discovered that babies felt a sense of ownership over objects and would go into a “violent rage” when one of them was taken away. The term for this kind of behavior is called the “endowment effect.” In a 2008 experiment led by Princeton scientist Daniel Kahneman, volunteers were given a coffee mug. Once they had the mug in their possession, they were offered to trade it for a bar of chocolate. Most turned down the offer, preferring to keep the mug. A separate group of volunteers was given the chocolate bar first, then asked if they would be willing to part with it for the mug. Again, the majority of volunteers told the psychologists, “no deal.” Our possessions, it seems, become part of us.

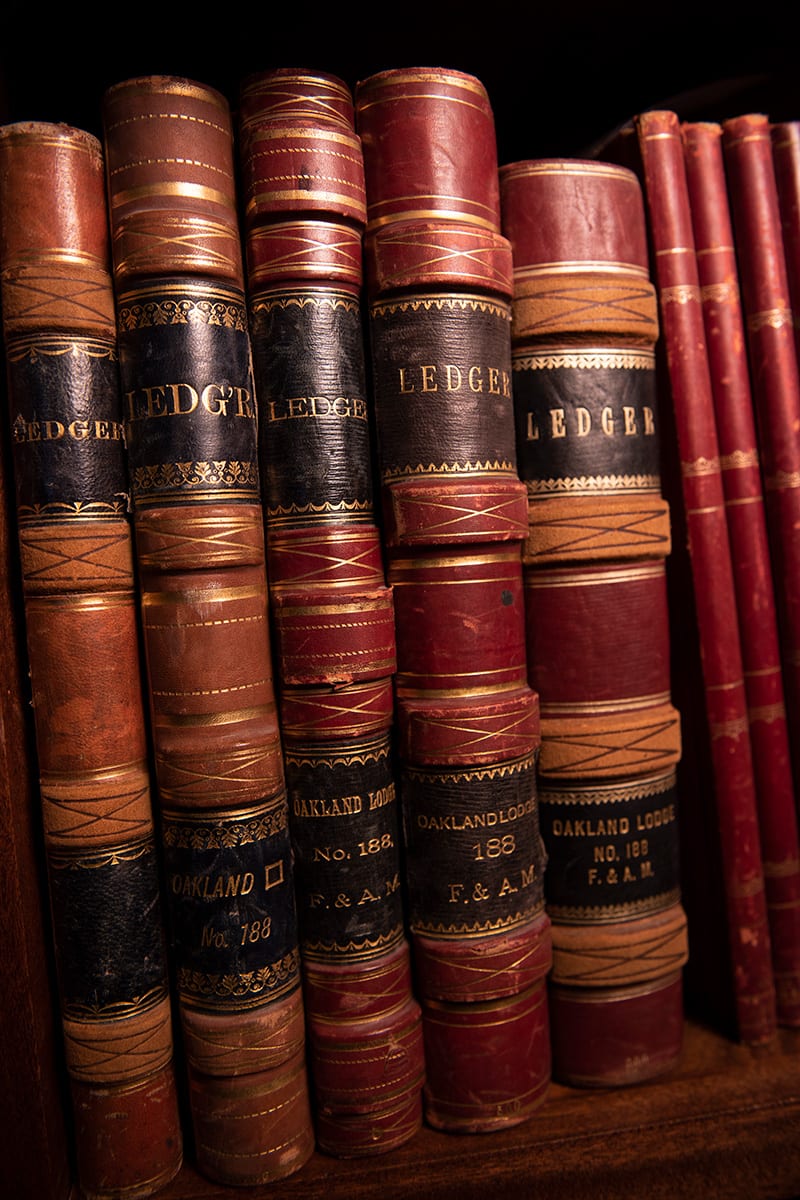

The longer an object is retained and revered, the more meaning it acquires. Culturally meaningful objects, like books, are containers for stories. In fact, before Gutenberg popularized movable type printing in Europe during the 1450s, objects took the place of books for people who couldn’t afford them; they served as reminders or prompts for stories that were important to a family or group. Just as an object can be infused with meaning for an individual, the same is true for groups of people with shared interests and beliefs. Young people wear T-shirts with the name of their favorite band as a way to send a signal to other fans: “I’m part of your tribe.” People attach stickers to the tops of computers to advertise their favorite websites, programming languages, and cryptocurrencies. The Zen monk in a saffron robe and a shaved head, the woman with a Prada handbag, the Orthodox Jew with a yarmulke, and the biker with a club tattoo are doing the same thing: They’re transmitting signals about who they are and what they believe and find valuable through the medium of material culture.

Material culture connects entire civilizations. According to many anthropologists, the circle of family, friends, and acquaintances that a person can reasonably have is limited to no more than 200 people or so. This limit is called Dunbar’s Number, named after anthropologist Robin Dunbar, who proposed the idea after he counted the number of relationships primates have and adjusted the number upwards in proportion to the average size of the human brain compared to other primates. It’s not possible to maintain stable relationships with more people than Dunbar calculated because we couldn’t bear the massive cognitive load required to deal with so many people on an intimate level. But material culture makes it possible for very large groups of people, including entire countries and religions, to share a common set of values and feel a kind of kinship even among strangers. You’ve likely experienced this phenomenon yourself when you see a stranger with a Masonic ring or pin – “There’s a brother. I don’t know him yet, but I already know we share a lot in common.”

You, too, undoubtedly own things that have little or no intrinsic value, but which you nonetheless consider priceless. It’s part of being human. The pioneering psychologist Jean Piaget discovered that babies felt a sense of ownership over objects and would go into a “violent rage” when one of them was taken away. The term for this kind of behavior is called the “endowment effect.” In a 2008 experiment led by Princeton scientist Daniel Kahneman, volunteers were given a coffee mug. Once they had the mug in their possession, they were offered to trade it for a bar of chocolate. Most turned down the offer, preferring to keep the mug. A separate group of volunteers was given the chocolate bar first, then asked if they would be willing to part with it for the mug. Again, the majority of volunteers told the psychologists, “no deal.” Our possessions, it seems, become part of us.

You, too, undoubtedly own things that have little or no intrinsic value, but which you nonetheless consider priceless. It’s part of being human. The pioneering psychologist Jean Piaget discovered that babies felt a sense of ownership over objects and would go into a “violent rage” when one of them was taken away. The term for this kind of behavior is called the “endowment effect.” In a 2008 experiment led by Princeton scientist Daniel Kahneman, volunteers were given a coffee mug. Once they had the mug in their possession, they were offered to trade it for a bar of chocolate. Most turned down the offer, preferring to keep the mug. A separate group of volunteers was given the chocolate bar first, then asked if they would be willing to part with it for the mug. Again, the majority of volunteers told the psychologists, “no deal.” Our possessions, it seems, become part of us. People in general don’t give much thought to their material culture. It’s actually a bit difficult to appreciate the material culture we are born into – the way we eat, sleep, socialize, work, decorate our homes, and dress are just the way things are; they are part of us and easy to take for granted, like the air we breathe.

People in general don’t give much thought to their material culture. It’s actually a bit difficult to appreciate the material culture we are born into – the way we eat, sleep, socialize, work, decorate our homes, and dress are just the way things are; they are part of us and easy to take for granted, like the air we breathe. Freemasonry emphasizes the importance of understanding and sharing the meaning of its unique, deliberately designed material culture. This same kind of awareness can extend beyond the lodge to the world at large. It’s a worthwhile exercise to go through your day being observant of the material culture of your family, your workplace, your place of worship, and your neighborhood. What parts of it hold special meaning to you? How do you use material culture as a way to find common ground with people outside your immediate circle? Are there any parts of material culture that you find perplexing – and if so, why? How can you use material culture to share meaningful stories with the people in your life, and ensure that those stories will outlive you so that others can benefit? Being aware of material culture and asking questions about it, even those that can’t be answered, make life more enriching and rewarding.

Freemasonry emphasizes the importance of understanding and sharing the meaning of its unique, deliberately designed material culture. This same kind of awareness can extend beyond the lodge to the world at large. It’s a worthwhile exercise to go through your day being observant of the material culture of your family, your workplace, your place of worship, and your neighborhood. What parts of it hold special meaning to you? How do you use material culture as a way to find common ground with people outside your immediate circle? Are there any parts of material culture that you find perplexing – and if so, why? How can you use material culture to share meaningful stories with the people in your life, and ensure that those stories will outlive you so that others can benefit? Being aware of material culture and asking questions about it, even those that can’t be answered, make life more enriching and rewarding.