Generations Connected

Two senior DeMolays, and current Masons, share their impactful experiences and perspectives of these Masonic fraternal orders.

By Drea Muldavin-Roemer

At 12, Casey developed an acne problem. At first it seemed like no big deal – just a few red spots. But as the spots spread over her face, everyone seemed to notice them. Kids at school asked if she had chicken pox or allergies. They began to chide her when she ate chocolate or chips, making fun of both her skin and the shape of her body.

Overnight, she’d gone from being invisible to being bullied. And, it didn’t get better when she left for the day. The other girls began excluding her from the Snapchat photos they took during homeroom. They left comments on her Instagram page, like – “Ew, go buy Clearasil!” But Casey had tried all the over-the-counter medications and nothing helped. She began feeling very alone – it was just her, her bad skin, and a computer screen filled with jokes of which she was the punch line.

According to Sheening Lin – a psychologist with 15 years of experience and director of programs for the Masonic Center for Youth and Families – stories like Casey’s are all too familiar. The most common concerns facing today’s youth are depression and anxiety, and particularly anxiety related to social interaction and social media. “Kids often won’t disclose when they’re being bullied online,” he says. “They might feel embarrassed or ashamed at how upset they are. Posts often disappear, and it’s hard for them to show proof.”

As an entire generation grows up in the digital world, the conversation around what should be private and what should be shared is ongoing. While some kids might have traditional notions around privacy, others might feel that anything is game for public viewing. “Parents need to initiate open communication and determine what standard of privacy is appropriate for each child,” Lin says.

He encourages parents to make sure that their children’s online settings and privacy options are in alignment with what they feel is appropriate. Parents can always reassess several months later to see if certain liberties can be expanded, giving youth a sense of empowerment and earned privileges. “It can require a little bit of give and take,” he explains. The important thing is for youth to know that their parents might be checking up on their activity every so often to be sure they are following the agreedupon guidelines.

An important part of MCYAF’s work is helping youth build emotional resilience and the knowledge of when to ask for help. In 2018, the Center reached nearly 800 Masonic youth in DeMolay, Job’s Daughters, and Rainbow for Girls during anti-bullying workshops that were held throughout the state.

Lin has noticed that Masonic youth are already quite vocal with one another about social issues – perhaps more so than kids in the general population. “There’s already a level of peer support that they are building,” he says. Rather than personal experiences of being bullied, the youth tend to focus on what to do if they encounter others who are being intimidated.

So, MCYAF’s workshops help youth identify when bullying might be happening and how to interrupt it. Lin calls it being a “positive deviant.” “Sometimes diffusing a situation can be as easy as owning what is happening,” he explains. “If kids see someone being bullied and they say, ‘Hey, you can’t say that. It’s not OK to talk to him like that,’ the bully will oftentimes stop.”

"Your kids are going to be watching to see if there’s an openness in the home to talk about these things, and it’s important to get across to youth that they don’t have to feel alone or like they just have to let it pass."

But, he points out, there is a wide range of comfort around being an actual disruptor during a moment of bullying versus offering support after the fact to someone who has been a target. “With cyberbullying being a bigger concern,” he says, “how to be a disruptor in cyberspace is a different can of worms… the way in which people can retaliate immediately requires some extra thought.”

MCYAF’s goal is to give young people the knowledge they need to maintain a sense of emotional safety out in the world so that they can thrive as leaders and promoters of positive change.

Families need to foster open communication so that kids feel comfortable discussing problems with their parents, and parents can approach their children effectively and compassionately if they notice signs of suffering or isolation. Not every child is going to disclose to their parents when they’ve been bullied. It is important for parents to feel comfortable asking their children what might be going on if they notice something is off. These questions don’t have to be pointed, Lin says, but showing active concern goes a long way.

Taking the first step to create dialogue can be challenging for some parents. Youth often have a greater understanding of emerging media platforms, and it can be difficult for parents to stay on top of a constantly shifting landscape of services they don’t use. They may also struggle with trying to juggle how to encourage their children’s individuation while setting clear and consistent boundaries.

Lin encourages parents to feel empowered in knowing that they set the tone for discussion. “Your kids are going to be watching to see if there’s an openness in the home to talk about these things,” Lin says. “It’s important to get across to youth that they don’t have to feel alone or like they just have to let it pass.” Lin also wants to remind parents that most schools take cyberbullying very seriously, so they can take advantage of a network of support outside the home.

As for society’s role in helping youth, encouraging accountability is crucial. He has seen how conversations surrounding accountability have encouraged dialogue between Masonic youth in the workshops MCYAF has hosted. Most Masonic youth are already socially conscious, invested in making a difference among their peers. DeMolays are starting to openly discuss issues surrounding the nuances of language and sexual consent, and are exploring their responsibility in creating a harassment-free environment. They recognize that talking to other young men and holding each other accountable is a crucial part of this narrative.

The Masonic Center for Youth and Families is clear in its mission to support youth and family in creating a society where abuse of power and bullying are not tolerated. When it comes to the future, it takes a village – of educators, parents, mentors, and Masonic leaders – to buttress the next generation to forge a more compassionate path.

The Masonic Homes established the Masonic Center for Youth and Families (MCYAF) in San Francisco’s Presidio in 2010. Originally offering individual and family therapy based on a conventional therapeutic model, the Center has expanded to Covina and now offers everything from traditional therapy to educational counseling to testing for learning disabilities and cognitive issues. Serving both Masonic clients and the general public, it also offers telehealth services across California.

Contact MCYAF: mcyaf.org

(877) 488-6293 (San Francisco)

(626) 251-2300 (Covina)

Two senior DeMolays, and current Masons, share their impactful experiences and perspectives of these Masonic fraternal orders.

Track DeMolay’s expansion from the United States to Canada, Europe, and beyond.

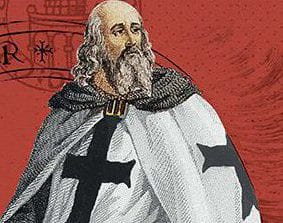

The historic namesake of the order of DeMolay carries with it a fascinating history that has long piqued curiosity and study.