Timothy Pflueger, the Invisible Hand Behind San Francisco’s Skyline

With his Jazz Age flair, architect Timothy Pflueger brought a signature style to San Francisco’s skyline.

By Jackie Krentzman

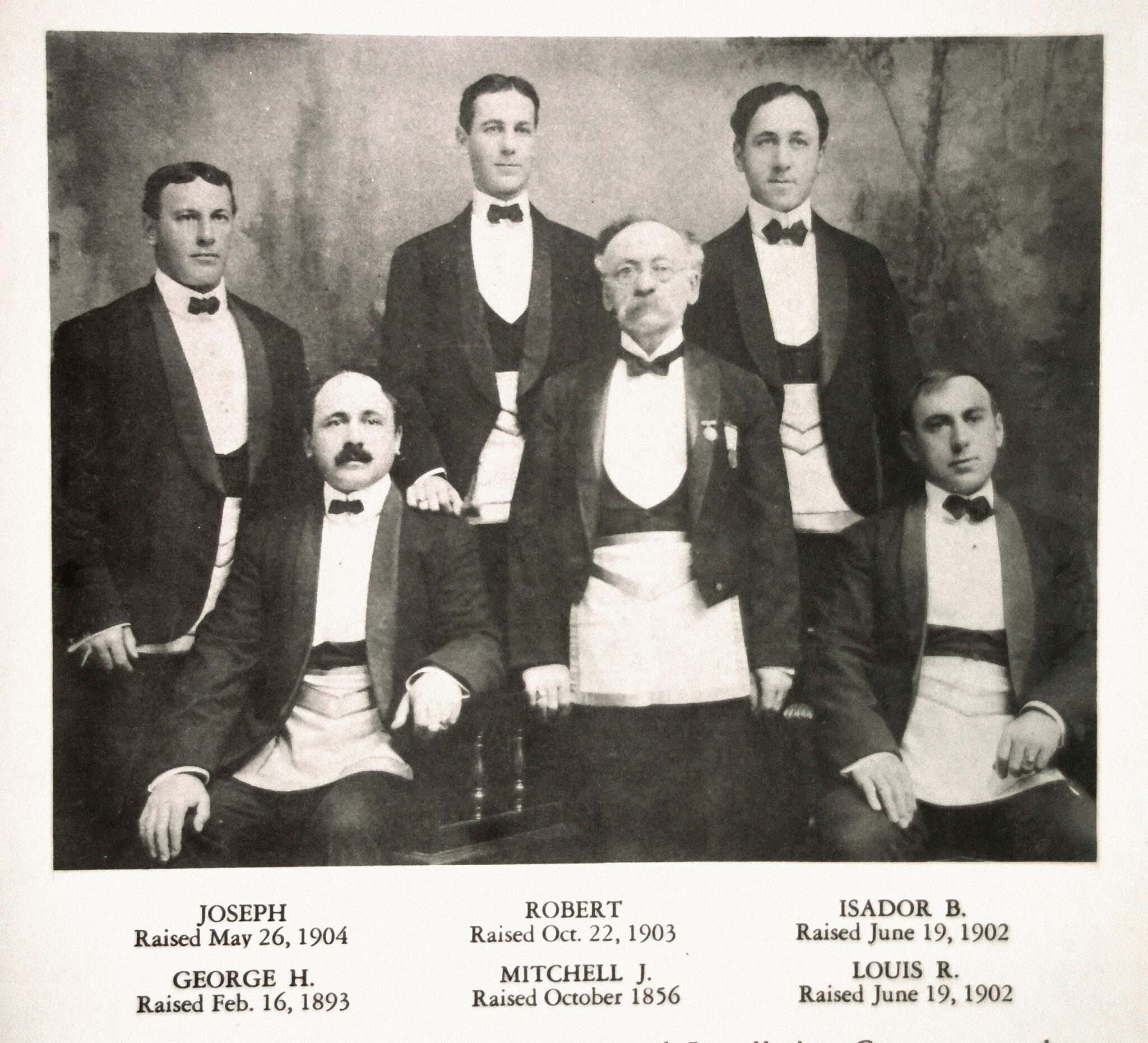

Of all the groups of fortune-seekers that rushed to San Francisco in the 1850s, perhaps none can be said to have thrived as much as the city’s Jewish immigrants. There, they were accepted into the political and cultural fabric of the city to a greater degree than perhaps anywhere else in the United States, helping to establish an influential community that flourished throughout the 19th and early 20th century. Nowhere was that more visible than in the city’s Masonic lodges—and in particular, the lodge room of Fidelity № 120.

Today, Fidelity Lodge is long gone. (It’s now part of San Francisco № 120, the result of a consolidation in 2008). As a result, the lodge’s local history, and particularly its role in the rise of San Francisco’s Jewish community during the city’s Gilded Age, has largely been obscured. However, as the center of Jewish Freemasonry at that time, Fidelity № 120 should be remembered as one of the important institutions of San Francisco’s Jewish life. In that way, the lodge played a big part in setting the course of the city’s religious and cultural history.

From the start, the city’s Jewish population forged a distinct path. Rather than set out for the mining camps of the Sierra foothills, the first wave of Jewish arrivals—many hailing from the German region of Hesse and the state of Bavaria—instead launched businesses to serve the influx of prospectors with the goods and tools they needed to mine for gold. In short order, a thriving community of Bavarian-Jewish entrepreneurs had established itself as integral to the young city’s business class.

That was reflected in the city’s early Masonic lodges, in which Jewish members were particularly well-represented. Among the prominent Jewish Masons of the first decade were Benjamin D. Hyam, founding master of Benicia № 5 and the state’s third grand master; Adolphus Hollub, a successful dry goods supplier and, fraternally, grand lecturer and senior grand warden in 1852; and William Schuyler Moses, a charter member of Golden Gate № 30 in 1853. Other notable Jewish members included Joel Noah, a well-known clothier, founding member of California № 1, and longtime tiler of the lodge; and Rabbi Abraham Labatt, the first president of Temple Emanu-El and master of Davy Crockett № 7 in 1850.

It’s not necessarily surprising those figures would be welcomed into lodge; Freemasonry, as an ecumenical tradition, has always been open to men of all faiths. In fact, across the country, at least 24 Jewish Masons served as state-level grand masters in the U.S. during the 19th century. What’s more surprising, in the case of San Francisco, is how significant the Jewish influence on the local fraternity was, says Fred Rosenbaum, author of Cosmopolitans: A Social & Cultural History of the Jews of the San Francisco Bay Area, considered the definitive history of San Francisco Jewish history. “It shows the open atmosphere and relative lack of anti- Semitism at that time in San Francisco,” he says.

According to Anthony Fels, professor emeritus of history at the University of San Francisco, out of 13 English-speaking lodges in San Francisco in the late 19th century, at least six had significant Jewish memberships. (Another lodge, the French-speaking La Parfaite Union № 17, also included several Jewish members, likely immigrants from the Alcase region.) He further estimates that 12 percent of San Francisco’s Masons of the era were Jewish—almost double their share of the city’s overall population at the time. “The extent of Jewish inclusion seems very substantial indeed,” he writes.

Another reason the prosperous Jewish middle class joined San Francisco’s Masonic lodges was that it was still often excluded from other organizations, such as the venerable Bohemian Club. And unlike the B’nai B’rith—a Jewish men’s fraternity, which launched its first San Francisco chapter in 1855— Masonry provided the opportunity to intermingle with the city’s mostly Protestant establishment. Generally, most San Francisco Masons, including its Jewish members, were in similar mercantile occupations— insurance brokers, factory owners, dry-goods importers, and so on. “Belonging to a Masonic lodge was a step to assimilation,” Fels says.

While nearly all of San Francisco’s lodges had at least some Jewish members, it wasn’t until 1858 that there could be said to be a truly “Jewish lodge.” That was when a group of members split away from Lebanon № 49 to form Fidelity № 120. Its first master was Louis Cohn; Fred A. Benjamin was its inaugural senior warden and Seixas Solomons the first junior warden. All three were prominent San Francisco Jewish businessmen and, at least in the case of Solomons, part of the city’s pioneer generation. (In fact, Solomons belonged to a truly impressive family: His grandfather had been a rabbi and leader in the American Revolution; his son, Theodore, was one of the first explorers of the Sierra Nevada mountains; and his daughter, Selina, was one of San Francisco’s leading suffragettes in the early 1900s.)

The driving force behind the lodge, however, was Moses Heller, who was master in 1867. The Bavarian-born Heller, who ran one of the largest dry-goods businesses on the West Coast, created the lodge’s widows and orphan’s fund and served as grand treasurer for nine years.

Fidelity grew rapidly, from its original 33 members to 130 just a decade later, eventually peaking at 551 in 1950. Unfortunately, Fidelity was one of the many San Francisco lodges that lost its records in the earthquake and fire of 1906. As a result, its early rolls have been lost, making a full accounting of its history impossible.

However, obituaries and other historical sources paint a tantalizing picture of Fidelity Lodge’s membership. Among its early members were Julius Platshek, a wealthy real estate mogul who lived at the Palace Hotel; Mendel Esberg, a cigar merchant and manufacturer who served a term as master of the lodge; and Julius Jacobs, a merchant who helped lead the free kindergarten movement on the West Coast and who was later appointed by President McKinley as assistant U.S. treasurer. There was also Michael Goldwater, founder of the Goldwater’s Department Stores. (Goldwater’s son, Morris, would eventually become Grand Master of Arizona. Michael was also the grandfather of Sen. Barry Goldwater.) In later years, members included Isaac Strasburger, the financier, oil tycoon, and charter member of the San Francisco Stock Exchange.

Other known members point to how closely related the lodge was to the city’s preeminent synagogues. For instance, Elkan Cohn, who succeeded Abraham Labatt as the second rabbi of Temple Emanu-El, the influential German-Jewish reform synagogue, was a member of Fidelity № 120. So too was Jacob Voorsanger, the nationally renowned rabbi who took over from Cohn. In fact, Voorsanger served as grand orator for the Grand Lodge of California in 1885 and as grand chaplain in 1889. Two other members of the lodge, Henry A. Henry and Jacob Nieto, were rabbis with the city’s other main synagogue, Sherith Israel, which was originally an Orthodox congregation comprised of mostly Polish Jews.

Beyond the business, political, and social connections offered to Jewish Masons through the lodge, Rosenbaum and Fels note how the tenets of Reform Judaism, which was fast taking hold in San Francisco at the time, dovetailed with the principles of Freemasonry. Both Masonry and the reform Jewish movement in the 19th century “emphasized monotheism, the Old Testament, and Enlightenment ideals such as logic and reason,” Fels says.

One of San Francisco’s early Jewish newspapers, The Hebrew, published a column in 1865 exploring similarities between Judaism and Freemasonry. It noted the resemblance in forms of worship, rites, and ceremonies, their focus on monotheism, and even the construction and orientation of lodges and synagogues.

Perhaps the most significant commonality between the two traditions, however, was their focus on service to others—represented by the concept of Tikkun olam, or repairing the world. “Both [Masonry and Judaism] hold the basic belief in the goodness of humanity under God’s guidance,” Fels says, “the importance of being charitable to one’s neighbors, and doing good works in the community.” In that light, he says, the connection between San Francisco’s Jewish and Masonic cultures isn’t just a historical curiosity. Instead, “It made a lot of sense.”

Photography by:

Henry W. Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry

With his Jazz Age flair, architect Timothy Pflueger brought a signature style to San Francisco’s skyline.

At the French-speaking La Parfaite Union No. 17 Masonic lodge, in San Francisco, a Francophone legacy lives on.

Tips and advice for providing care to aging parents, from the experts at the Masonic Outreach Services team.