Digging Up the Past at a Masonic Cemetery

Researchers hope to uncover local history within the small Gold Rush-era Jamestown Masonic Cemetery.

By Ian A. Stewart

Above: The Prince Hall Apartment complex in San Francisco’s Fillmore District, which was sponsored by the historically Black fraternity, included 91 units of federally subsidized housing—part of the controversial redevelopment of the city’s Western Addition neighborhood in the 1960s and ’70s.

Although Prince Hall Masonry can trace an unbroken history in San Francisco all the way back to 1852, there’s scarcely any official acknowledgement of its long presence in the city. None of its lodges are deemed historic landmarks, no bronze plaques exist to mark its meeting spaces, and no streets or neighborhoods are named for it. Instead, the most significant structure bearing the name of the historically Black fraternity is a nondescript low-income apartment complex in the Fillmore. That may register as a surprise, but it’s somewhat appropriate: The story of the apartments’ construction encapsulates much of the African American experience in the Bay Area, for better and worse.

Today, the Prince Hall Apartments, a federally subsidized housing development completed in the 1970s, remain a testament to a painful era in the city’s history, during which San Francisco’s Black population suffered a mass displacement from which it never recovered. However, the history behind those homes shows that nothing is ever quite as simple as black and white.

Originally, San Francisco’s Prince Hall lodges met in North Beach, eventually moving, post-WWII, to a modest Victorian residential building at 2804 Bush Street. At the time, the Fillmore neighborhood was the center of the city’s Black community, with a buzzing commercial corridor known as the “Harlem of the West” for its bustling jazz scene. Between 1940 and 1950, the Black population of the area swelled from 2,000 to 15,000.

Despite that growth, the area was one of the first targets of the city’s newly established Redevelopment Agency for urban renewal, which aimed to bulldoze what it described as a “blighted” ghetto. The plan was part of a nationwide “slum clearance” undertaken in the hopes of stemming the middle-class flight to the suburbs. Almost as a rule, these redevelopments were focused on low-income and nonwhite neighborhoods. In San Francisco, the Fillmore was ground zero for redevelopment.

The ambitious project was slow to develop, and then came on fast. The first shovels went into the ground in 1958, and within a year some 28 blocks of mostly dilapidated Victorians and modest storefronts were demolished, replaced with high-rise towers and the new, six-lane Geary Expressway. It’s estimated that 8,000 residents of the Western Addition were displaced as a result, including entire swaths of the majority-Black Fillmore and the Japanese Nihonmachi area across Geary. A great many of those former residents never returned, while others reported being intimidated into selling their homes under market value or under-compensated for their lots.

That experience led to significant community opposition to the plan. As a result, the second phase of the project, launched in 1963, involved far more concessions to local residents, many of whom organized alongside labor and neighborhood groups. For instance, the city agreed to set aside 30 percent of all new units for low-income residents, and to guarantee displaced residents a spot in the new buildings. Rents in the new housing projects were capped at $185 a month for a four-bedroom unit, with federal subsidies bringing that number much lower for some.

Community-based groups were also invited to bid on many of the individual developments. Backed by financing secured under the National Housing Act, groups including Bethel AME church, the Construction and General Laborers Union Local № 261, and the Seventh-day Adventist Church each sponsored housing developments within the zone. The Most Worshipful Grand Lodge of Prince Hall Masons, located just a stone’s throw away on Bush Street, submitted its proposal in 1966 and, a year later, Redevelopment Agency head Justin Herman, speaking as a guest of honor at its annual Grand Session, announced the fraternity had been awarded the project to develop Block 773, bounded by Golden Gate Avenue, Fillmore, McAllister, and Webster streets.

Above: Prince Hall Grand Master Harry A. Brewer (center) is joined by Mayor Joseph Alioto (right) and Redevelopment Agency head Justin Herman at the groundbreaking for the Prince Hall Apartments in 1970.

It’s not entirely surprising that Prince Hall Masons of the era turned to home-building. The fraternity in the late 1960s was especially keen on such programs: It developed two small apartment complexes in San Diego, the Euclid Apartments and the Prince Hall Apartments, under the supervision of Past Grand Master Paul E. Washington. And in 1969 it partnered with two other nonprofits to sponsor the 21-unit Hoover Senior Housing apartments in Los Angeles using federal financing. Years later, it would develop similar plans in Oakland and Berkeley, although the latter project stalled out. Even earlier, in the 1950s, the fraternity purchased land for a senior home in Tulare County. Additionally, the fraternity in 1952 launched the Prince Hall Credit Union to provide loans to members at a time when discrimination against Black Americans in housing and banking was all too common.

The apartment development can also be seen as an example of the fraternity’s growing social and political capital. By the 1960s, San Francisco boasted eight Prince Hall lodges (in order, Hannibal № 1, Victoria № 3, Bayview № 64, Jerusalem № 72, Twin Peaks № 80, Charles H. Tinsey № 92, George W. Wilson № 101, and Chester A. Girard № 106) and had around 7,000 members on its rolls. Across the bay in Oakland, another 10 lodges had been established. That made Prince Hall an organizing force within San Francisco’s still-small Black community—which peaked at about 13 percent of the city’s overall population.

With the Prince Hall Grand Lodge acting as sponsor (and board of directors head John Wiley as lead), the apartment project called for a village-like complex of low- and moderate-priced homes, ranging from studio units to 3-bedroom models. The endeavor was the first in San Francisco to be both designed and built by Black-owned architectural and construction firms. In the first case, that fell to the outfit of Robert Kennard and Arthur Silvers, influential Los Angeles-based architects who’d been inspired by modernist designers including Richard Neutra. The pair had also developed the Watts Happening Cultural Center in Los Angeles, the Temple Akiba synagogue, and several local schools around L.A. Kennard was also responsible for much of the Thurgood Marshall College at UC San Diego, while Silvers, who’d been chairman of the Congress of Racial Equity in L.A. in the 1960s, designed the Strawflower Shopping Center in Half Moon Bay. The Winston Burnett Construction Company, one of the few Black contracting firms in San Francisco at the time, was responsible for the building of the apartments, hiring as many as 100 workers, nearly all Black, and many of whom were trained on the job. In all, the project cost $1.8 million ($149 million today).

On June 27, 1970, Prince Hall Grand Master Harry A. Brewer, in full Masonic regalia, joined Herman and Mayor Joseph Alioto to drive the ceremonial first shovels into the ground. The development, which would include 91 units and parking for 72 vehicles, was opened in 1972.

For more than 20 years, the fraternity operated the low-slung apartments at 1170 McAllister Street. However, financial challenges in later years forced the Department of Housing and Urban Development to take over responsibility for the loan from the fraternity, and in the 1990s, the complex was sold to Bethel AME. That church, with its deep roots in the Western Addition neighborhood, had previously constructed the Friendship Manor development immediately adjacent to the Prince Hall Apartments, running it as a co-op owned by its parishioners. Around the same time, the church also took ownership of the nearby Freedom West, Laurel Gardens, and Thomas Paine apartment blocks. In so doing, the church has helped the community retain a toehold in the rapidly changing city.

In the end, the redevelopment program was seen as a massive failure, one that nearly wiped out the city’s Black community and decimated what had once been a vibrant, if poor, neighborhood. Nearly 15,000 people were displaced from the Western Addition, 60 percent of whom never returned. Almost three-quarters of Black-owned businesses in the area were permanently closed. Out of about 22,000 Black residents that lived in the Fillmore in 1970, there are now just 6,000. What had once been the Harlem of the West was reduced to yet another poor neighborhood, but no longer a cultural mecca.

Standing at the very heart of that effort, the Prince Hall Apartments are a reminder of the area’s proud and troubled past—and the complicated legacy that would define its future.

Photo courtesy of:

San Francisco Public Library, S.F. History Room

KPIX/Bay Area Television Archive

Researchers hope to uncover local history within the small Gold Rush-era Jamestown Masonic Cemetery.

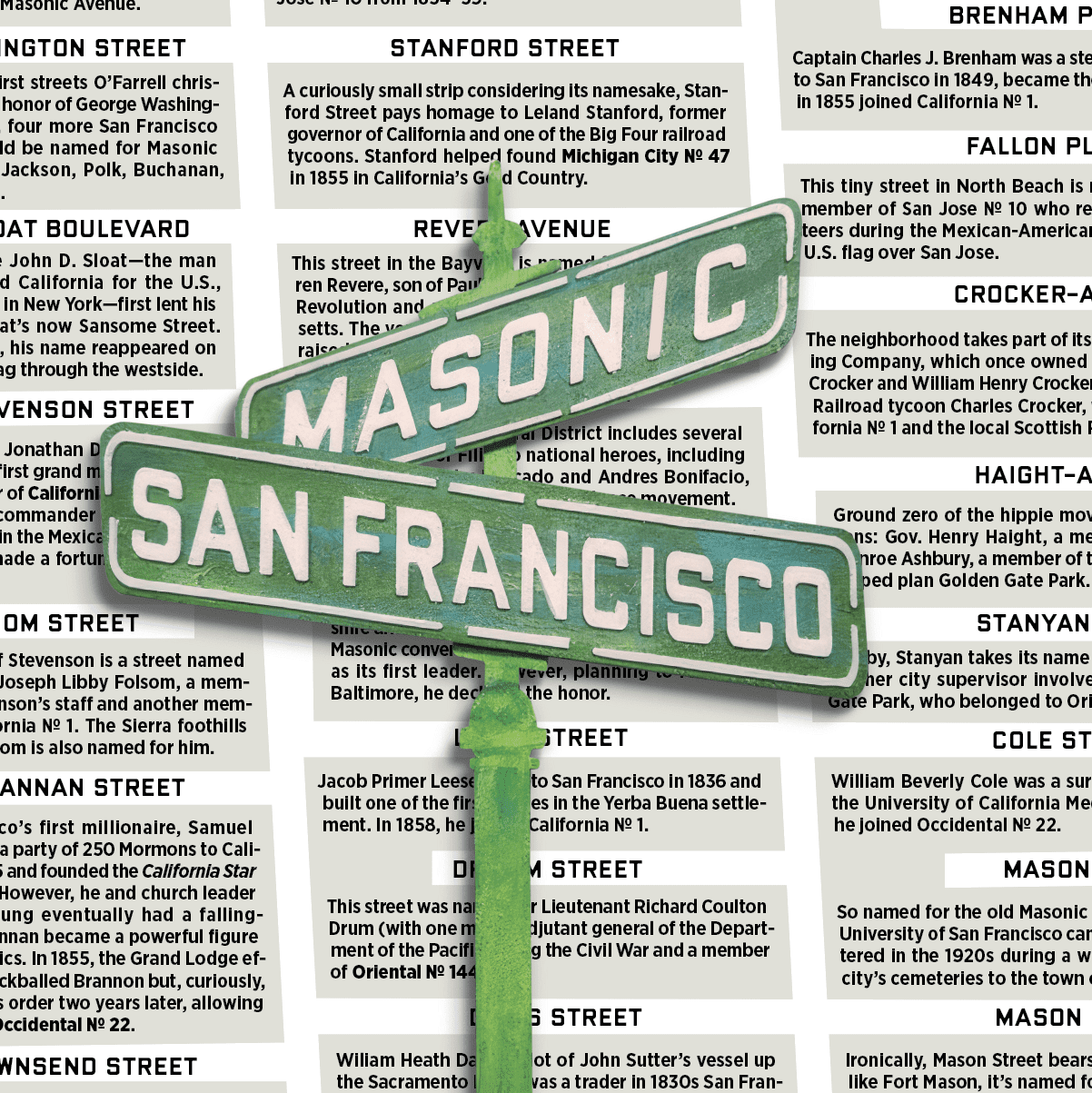

Throughout San Francisco, street names share subtle reminders of a fraternal past.

Meet Jeffery Mendez, a Mason combining cookouts and camaraderie.