A Healing Ceremony for Paradise Masons

In Paradise, Table Mountain No. 124 is helping a community move forward.

By Ian. Stewart

Over the three decades from the 1970s to the turn of the century, there was a 50 percent decline in the number of Americans who assumed a leadership position in a local organization. There was a 35 percent drop in church attendance and a 40 percent slide in the number of Americans who went to even one public meeting. Membership in the national PTA dropped from 12 million to 5 million. For the Masons of California, membership has fallen from a high of over 244,000 in 1965 to about 40,000 today.

By virtually any measure, Americans over the past half-century have stopped joining clubs. The result of that mass drop-out has been catastrophic, according to Robert Putnam, the Harvard sociologist who popularized the concept of social capital in his 2000 book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. As Americans stopped making connections to their neighbors, he argues, we became increasingly isolated and polarized.

Today that trend appears to have reached crisis proportions—and a new generation is looking for answers. For filmmakers Pete and Rebecca Davis, that led them back to Putnam’s Bowling Alone and the hiding-in-plain-sight importance of social clubs. The result is Join or Die, a new documentary that traces Putnam’s work over half a century and makes a powerful case for the value of social and civic clubs. “To tackle today’s challenges, we need millions of Americans to become joiners,” Pete Davis explains in the film.

Here, co-director Rebecca Davis explains what drew her to rural lodge rooms, church picnics, and other meetups, and how she became an evangelist for membership of all stripes.

You co-produced this film with your brother, Pete. What attracted you to this idea of the role of social capital in civic life?

We first approached Robert Putnam in 2017, as he was about to retire from teaching. That seemed like a moment he might be able to look back on his career and potentially do a documentary for the 20th anniversary of Bowling Alone.

My brother was a student of Robert’s, so he had a personal connection. I was working as a TV journalist for NBC News, covering things like school shootings, the opioid epidemic, veterans coming back and feeling kind of at a loss for community. For me, I got to a place where I felt I couldn’t keep covering these symptoms. I needed to zoom out and try to find some solution-based story idea I could work on.

Join or Die is a pretty grabby title. In the film, you link social clubs with the very future of our democracy. Did you feel this was a real existential threat?

Our title has been a little controversial to some people, but yes, the stakes are that high—even for joining a bowling league or, as people have pointed out, maybe today it would be a pickleball league. It’s no small thing to have a space where you can have fun, meet people, and improve your mental health.

That’s what drew us to Bob’s work. It’s about lifting up the bowling club and the church bake sale, which are important not only for our personal health and well-being, but also for that secondary meaning behind our title, the health of our democracy.

It’s in those spaces that we learn to practice ways to be shared co-creators in the world that we’re building. And a lot of what’s happening today, especially online, is anti-that.

Above: Bowling leagues suffered a massive drop-off in popularity, even though as a sport, bowling remains popular.

Bowling Alone is nearly 25 years old. As much as the idea of social capital has entered the mainstream, it feels like we’re moving in the wrong direction, with higher rates of loneliness and social isolation. Why do you think this trend has been exacerbated?

Bowling Alone came out in 2000, right about the time Facebook was launching. So one question at that time, as this new technology was coming on the scene, was whether it could be a place to look for a solution to these trends. But there is no silver bullet. Facebook did not solve our community crisis.

These days, a lot of people say it’s the smartphones that are to blame, and that this is a new phenomenon. Something we were drawn to in Bob’s work is that it draws a much longer trend line, measuring social capital back to the 1960s and even earlier, to the turn of the last century and the Progressive Era, when many of these clubs were founded. So we were interested in revisiting that work for a new generation, at a time when it feels more relevant than ever.

You’ve hosted several screenings of the film for community groups. What kinds of people have shown interest in this work?

We’ve done about 300 community screenings since we premiered the film in 2023. The majority of those were for groups of 25 or less. The surprising thing has been just how many people are hungry for this idea right now. We had one small-town mayor in California reach out because he wanted to use the film for wildfire preparedness, with the thought that neighbors who are closer and more in touch are easier to mobilize in the event of a big fire.

Then of course there are the usual suspects, the federated societies—the Rotary, the Elks, the Masons, the Odd Fellows. But there were also newer clubs and parents’ groups. In Austin, Texas, we hosted a queer skate club. The California Planners’ Association spoke with us about how we can design our cities to be more communal. And we screened it in Congress.

Above: The film profiles a lodge of Odd Fellows in Waxahachie, Texas.

Not all the groups you profile in your film are classic civic groups like the Masons. What made you choose these subjects?

It’s hard to sum up what a community looks like. We zeroed in on six community groups, including a mutual-aid group in Los Angeles as well as the Gig Workers’ Alliance in Chicago for rideshare workers. We had spreadsheets of like 300 groups we were looking at. But the takeaway from the ones we felt were doing this right was that they were all really rooted in place as the connecting factor bringing people together.

So often, we see things through a lens of left/right, and for a lot of people that’s become their main identifier. If we want to fight this moment of hyper-polarization, we need to have multiple layers of identity for people to latch onto.

We met a lodge of Odd Fellows, and they don’t talk about politics in their meetings. A lot of them said they don’t even know the political identity of the people they’re meeting up with, but they know they’re passionate about the place they live in and want to make it better. They understand the shared goals they’re working on.

An interesting distinction that Putnam makes is between “bonding social capital” and “bridging social capital,” where bonding is between people who are alike and bridging is between people who are different. The film doesn’t dwell on this distinction. I’m curious if you have thoughts about that.

The reality is that we need both in our democracy. In some of these groups, there’s bridging happening beneath the surface. In a bowling league, it looks like it’s just for fun, but there’s an incredible amount of bridging capital happening between members of different economic groups, for instance between surgeons and carpenters. Bob is careful not to say that bonding capital is bad and bridging capital is good. We need both. Studies find that those with more bonding capital are also more likely to bridge.

Our goal was, with people who aren’t members of anything, we want them to take that first step. These can be places where we learn the skills to build bridging capital. You go to a meeting, you learn to introduce yourself, strike up a conversation—that might sound basic, but those are skills we need to be working on more. That’s how our social bridging is going to happen more easily. It’s what we need if we’re going to have a functioning democracy.

269,743 U.S. MEMBERS

7,154 U.S. CLUBS

International Growth

“Rotary currently has more than 1.2 million members who belong to over 45,000 clubs in almost every country in the world. Over the past 10 years, membership has been relatively stable, with some loss in the U.S. compensated by growth in other areas of the world.”

New Types of Clubs

“Within the past few years, we’ve introduced new ways to make Rotary membership and participation more accessible, including e-clubs that meet exclusively online, passport clubs that encourage members to visit other clubs, and corporate clubs for those working at the same company. Our members have also started cause-based clubs that offer ways to channel a shared passion. Meanwhile, Rotary’s 100-plus ‘fellowships’ provide people with a shared profession, hobby, or identity a way to connect with friends around the world while strengthening their skills and being part of a caring global community. Rotary’s 25 ‘action groups’ also offer a way to connect globally with experts to address many of today’s important issues. Anyone, not just Rotary members, can be part of our Action Groups.”

—MICHAEL VANDAM, ROTARY INTERNATIONAL MEDIA RELATIONS

178,030 ADULT MEMBERS

7,158 ADULT CLUBS

Membership Trends

“As with most volunteer organizations, membership has been declining for some time. Our membership high for Kiwanis was 324,542 in 1992. Today, we have clubs in more than 80 countries, so while some areas see an aging membership, many are getting younger and more service-oriented.”

Service First

“Decades ago, membership was seen as a networking opportunity. Now, it’s more about service and the mission. But members ultimately stay because of their experience within their own club. Time and time again, our members tell us they value the service component of what we do. A close second is the relationships and bonds built through membership.”

—BEN HENDRICKS, CHIEF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS OFFICER

4,641 MEMBERS IN CA

111 LODGES

Membership Flat

“Our members are aging, and we’re getting very few younger folks in. Our median age now is probably 70 or 75. But membership is holding steady—we have just under 5,000 members in the state. We get between 2,000 and 3,000 people joining every year, but the attrition rate is about the same. The year before last, we gained 207 people. Last year, we had a net loss of 23. Today, we have 111 lodges. Back in the 1920s, there were 500 Odd Fellows lodges in California!”

Focus on Fellowship

“The lodges that are prospering are the ones that are having big dinners and events like that. In Davis, which is one of our biggest lodges in the state, with 380 members, they’re much more into the social aspect—they have tennis clubs and different kinds of clubs and committees. Unfortunately, in certain ways, the [philanthropic] tenets of our organization seem to be waning.”

—BARRY PROCK, GRAND SECRETARY, IOOF OF CALIFORNIA

~5,000 MEMBERS

67 PARLORS (CHAPTERS)

Opening Up Membership

“Like so many others, we have an aging membership. In 2020, we were at 7,000 members, and that went down to 5,317 this April. So at our annual meetings, we changed our membership requirements for the first time to open up to any California resident who’s a U.S. citizen and believes in our mission statement, rather than having to be born in California.”

History, Friendship, Charity

“People join for a mixture of reasons. A lot of people want to join because they have an interest in California history and want to be part of a group that does historical research. But we also have a lot of people who just want to meet new people. Others come in because of our charities—we support three hospitals that do cleft palate surgery.”

—STEVE MCLEAN, GRAND PRESIDENT

In Paradise, Table Mountain No. 124 is helping a community move forward.

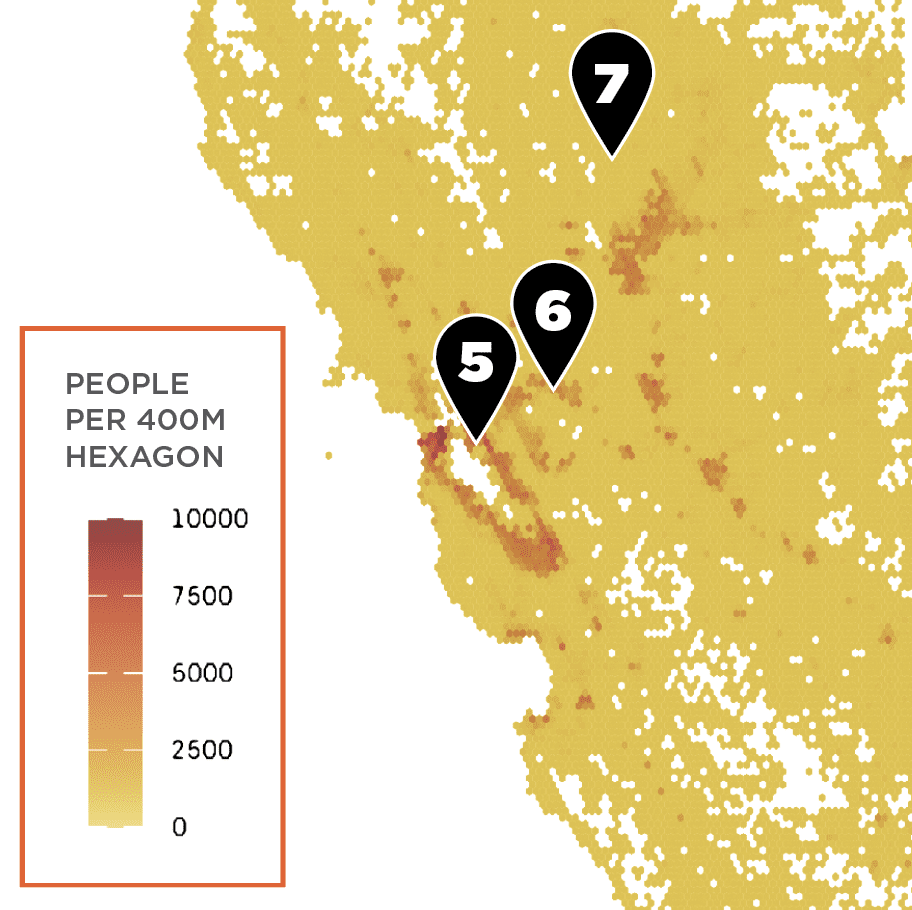

Grand Lodge’s New Lodge Development team gives a sneak preview of the areas they’re targeting for growth.

Shrouded in mystery and symbolism, the Order of Quetzalcoatl serves a decidedly philanthropic end.