In Prince Hall, Many Masonic Bodies, All Under One Banner

From the Eastern Star to the Prince Hall Shrine, exploring the many appendant bodies of Prince Hall Masonry in California.

By Grand Master David San Juan

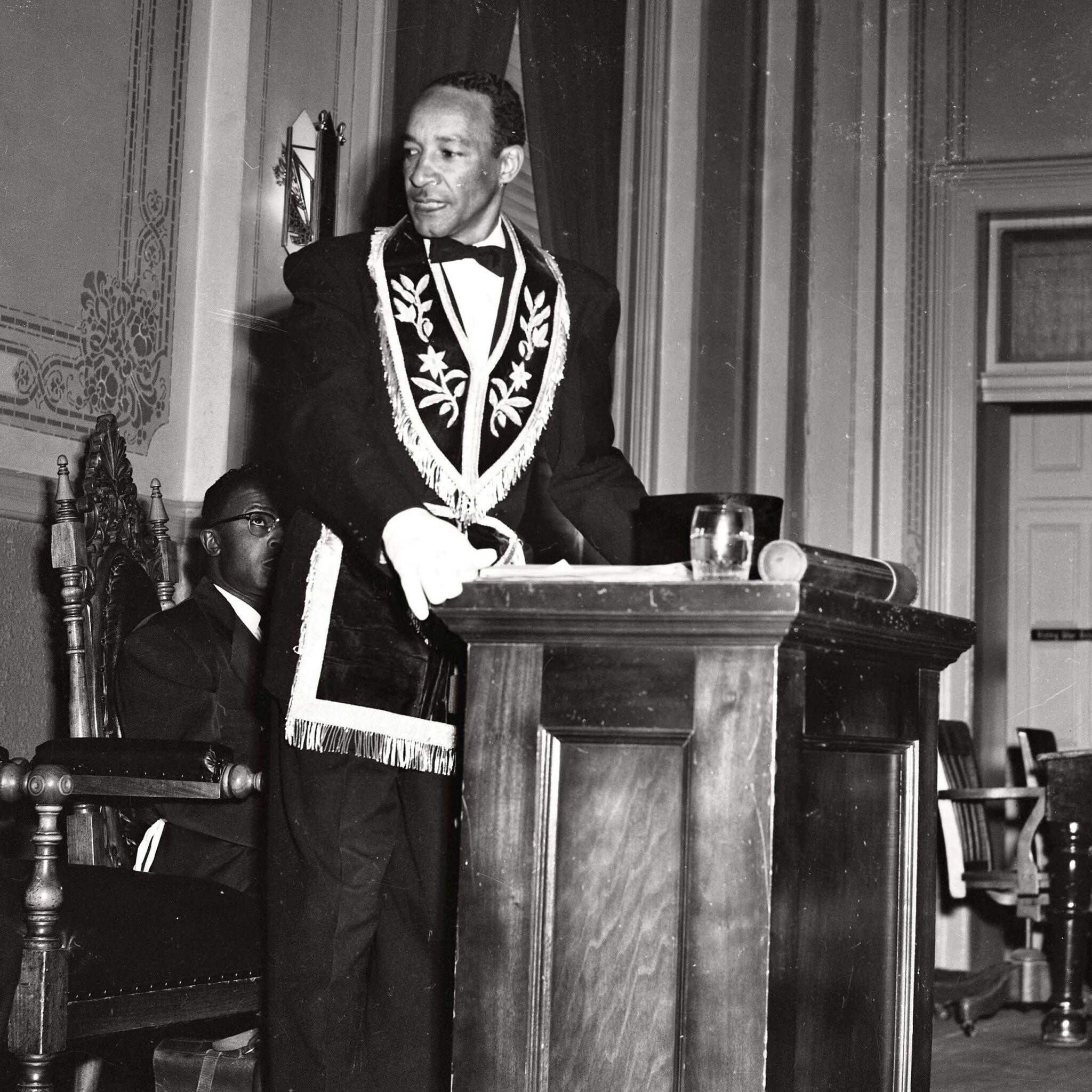

Above: An undated photo of California Prince Hall Masons during a ceremonial cornerstonelaying event.

For nearly 170 years, Prince Hall Masonry in California has provided its members with a place of belonging, even as those same people fought against and suffered discrimination in many other parts of their lives. The lodge has been—and still is—a venue to come together for personal betterment, for mutual aid, and for community.

That legacy is a proud one—and yet practically every history of Prince Hall Masonry begins not with its contributions to Civil Rights and the progress of Black people in America, but with something else entirely: the matter of its Masonic “regularity.”

For that reason, Prince Hall Masonry has two parallel histories: One in which it has played an important role in the civic lives of its members and Black communities more broadly, and another within the insular world of Freemasonry, in which it has been forced to advocate for its legitimacy.

For more than a century, that issue of “regularity” lingered over Prince Hall Masonry, used as a cudgel by those looking to denigrate the institution and deny Prince Hall Masons the benefits of membership in a worldwide fraternity. In California, for many years, the story was the same.

Partly, that is a reflection of the legacy of racism in this country that endures to this day. It is also partly due to the complicated history of 18th and 19th century Masonry, with its many schisms and reunifications (which occurred among all types of Masonic groups). In fact, the very founding of what would become known as the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California, back in 1855, came out of one such split among the descendants of Prince Hall’s African Lodge № 459. Still, the matter hangs over it like a cloud. As a result, virtually every history of the organization is required to include some attempt to trace its lineage back to African Lodge and ultimately to the Grand Lodge of England.

With that said, historians and Masonic scholars have already done this work and the result is clear: Prince Hall Freemasonry is considered “regular” and legitimate by practically every Masonic body in the world, including the United Grand Lodge of England and the Grand Lodge of California. Our state’s Prince Hall grand lodge is recognized by jurisdictions around the globe. The question of regularity is moot.

So, setting that to rest, we find that the history of Prince Hall Masonry in California is a fascinating one, and one that reflects the changing dynamics and positions of Black people in California. Through the development of Prince Hall Masonry here, we see a reflection of the advancement of civil rights, the Black community, and how it has endured through changing times and socioeconomic conditions.

Above: Members of a special committee launch a fundraising drive for “Prince Hall City,” a planned Masonic center in Los Angeles open to Prince Hall lodges and other related orders. The drive began in 1958.

As with so much else, that story begins in 1849 with the Gold Rush. Just as the Grand Lodge of California began in the campsite lodges formed by miners, so too did Black Freemasonry begin in the shadow of the Sierra foothills. The most important figure in this history was Philip Buchanan, the founder of Hannibal Lodge № 1 in San Francisco and the man who chartered the first three Prince Hall lodges in California.

Buchanan had been made a Mason in Pennsylvania before emigrating to California in 1850. He received his charter from what was then called the National Grand Lodge (which oversaw several state-level grand lodges of what we now call Prince Hall Masonry) to form Hannibal Lodge on June 15, 1852. The following year, the same National Grand Lodge issued charters for Philomathean № 2 in Sacramento and Victoria № 3 in San Francisco. Between June 19 and 23, 1855, representatives of the three lodges met in San Francisco to form a state grand lodge. Buchanan was elected as first grand master.

Meanwhile, three other lodges, Olive Branch № 5, Wethington № 7, and Mosaic № 11, had received charters from the African Grand Lodge of New York and were also working in California as the Conventional Independent Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons. It wasn’t until June 24, 1874, that the two groups were united under the name of the Most Worshipful Sovereign Grand Lodge of Colored Masons of California. This followed the dissolution of the National Grand Lodge, opening the door to reconciliation among the country’s Black lodges. (Nearly 20 years later, in 1893, a Prince Hall committee officially established that the California grand lodge would recognize the 1855 date as its inception.) In 1947, the name of the body was changed again to honor Prince Hall, a move made in collaboration with other state grand lodges.

That struggle to get established lasted well into the 20th century—thanks in part to persistent territorial fights with “clandestine,” or spurious, Masonic groups, some of which were little more than shams designed to defraud members out of their dues and charity dollars. In 1888, when St. John’s Lodge № 16 (later № 5) became the first subordinate Prince Hall lodge in Los Angeles, there were just eight constituent lodges and 126 total members in the state. The 1906 earthquake nearly wiped that out, destroying practically all of the grand lodge’s belongings and destroying its headquarters. (The organization did not carry insurance, and Grand Master R.C. Marshall refused offers of aid.)

Still, the organization persisted, and eventually began to grow during the years of World War I. From 1909 through 1929, the grand lodge chartered 25 new lodges, many of which were in the fast-growing southern part of the state, but also as far north as McCloud, in Siskiyou County (Pride of the West № 30), and even Portland, Oregon (Excelsior № 23). Membership rose from just 182 men in 1901 to 1,687 by 1921. In 1926, the grand lodge moved into its temple on East 50th Street in Los Angeles. But the real membership boom came in the wake of World War II, a period during which the African American population in California nearly quintupled. From 1941 to 1951, the number of Prince Hall Masons in California rose from 1,790 to 6,109. Thirty-eight new lodges were chartered between 1943 and 1954, including Puuloa № 51 and Cosmopolitan № 82, both in Honolulu. In 1951, the total assets of the grand lodge were reported at $205,036—a nearly tenfold increase from a decade prior.

As with nearly all Masonic groups in the United States, the midcentury represented the fraternity’s zenith. Women’s auxiliaries like the Order of the Eastern Star and youth groups including the Junior Masons and Order of the Knights of Phythagoreas were established throughout the state. With that, the organization’s ambitions grew. In 1931, Grand Master Theodore Moss approved the purchase of a 32-acre parcel just outside Tulare to be developed into a home for the fraternity’s aged and infirm, much like the Masonic Homes of California, and to establish a summer camp for children. That project ultimately languished, and the land was eventually sold off; however, the vision for a permanent apparatus for Masonic relief demonstrates the scale of the organization’s aims.

In addition to the network of mutual support that lodges offered one another, Prince Hall Masonry also took steps to formalize money lending. In 1952, the Rev. D.D. Mattocks helped lead the launch of the first Prince Hall Credit Union, which would eventually grow into a network of six such institutions throughout the state, each established to lend money to lodges and members of the fraternity at a time when many Black Americans did not have equal access to banking and lines of credit. These credit unions continued until 1989, when they were dissolved and placed into liquidation.

By the late 1960s, the fraternity had even turned to home-building: Using financing secured under the National Housing Act, the fraternity funded and constructed the Euclid Avenue Apartments in San Diego and the 92-unit Prince Hall Apartments in San Francisco’s Fillmore District, which broke ground in 1970—one of the signature projects of the infamous redevelopment of San Francisco’s Western Addition. As the historically Black neighborhood was systematically razed and rebuilt, the fraternity helped ensure a toehold for Black residents in the Fillmore. The project is now managed by Bethel AME, one of the longest-running Black churches in the neighborhood, and a close partner of Prince Hall Masonry.

The grand lodge’s interest in business endeavors like banking and home-building wasn’t simply financial. It also reflected the fraternity’s essential role in supporting the community it served and filling holes in the social safety net.

That work has led to a degree of political involvement within Prince Hall lodges that’s atypical of other Masonic organizations.

Particularly in the U.S. South, Prince Hall Masonry is inextricably linked to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Amos T. Hall, the longtime Prince Hall Grand Master of Oklahoma, and Thurgood Marshall, later to serve as U.S. Supreme Court Justice, were both lawyers with the NAACP, and through them and their connection to the Conference of Prince Hall Grand Masters, Prince Hall lodges throughout the country funneled more than $1.75 million in donations over a decade to the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund to help argue several court cases, including Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which ended school desegregation.

In 1960, Prince Hall grand lodges pledged to support and defend “every nonviolent demonstrator who requested our aid.” That statement, published in the California Prince Hall Bulletin, further read: “Our position as Free and Accepted Masons is, by belief and obligation, to work with the civil magistrates, local and federal, and, although from time-to-time we do not receive all that we feel and know our Constitution guarantees, we have that confidence that through Legal redress and within the framework of good government, in our time First Class Citizenship shall be attained.”

Locally, the fraternity also cast its eye on political matters where they concerned civil rights. In 1978, Grand Master Jessie B. Thompson was quoted by the Fresno Bee at the Prince Hall annual communication, saying, “In the past Masons have said, ‘Don’t get involved in politics.’ However, I feel we should get behind anyone who will champion our cause. The time has come when we must become more involved in the issues that affect us.” He cited upholding affirmative action and the appointment of Black judges to federal benches as two such matters.

That has led Prince Hall Masons both in California and elsewhere to more vocally support the candidacy of like-minded politicians. Certainly there has been a close connection between Prince Hall Masonry and some of California’s elected Black leaders. For instance, Tom Bradley, the former mayor of Los Angeles and the first Black mayor of a major U.S. city, was a Prince Hall Mason and spoke at the group’s annual communication in 1970. And Willie Brown, the longtime speaker of the state assembly and the first Black mayor of San Francisco, is a member of Hannibal № 1.

As both a vehicle for advocacy and a powerful network of support, Prince Hall lodges have helped make the voices of their members heard and felt.

As membership in the fraternity declined during the 1980s and 1990s, that visibility began to wane. However, Prince Hall Masonry remains vibrant and is well-positioned to remain so into the future.

One of the most significant developments in its recent history came in 1995, when the Grand Lodge of California and the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California made Masonic history by passing resolutions formally recognizing each other’s fraternal sovereignty. That move, which was several years in the making, allowed Masons from both groups to visit one another’s lodges and sit in on degree conferrals. It also put an end to what had been a century and a half of disunity.

Further, that effort, led by Prince Hall Grand Masters Herbie Price, Harold Mure, Joseph V. Nicholas, and Ronald Robinson, and California Grand Masters Charles Alexander, Stephen Doan, William Stovall, and Ron Sherod, opened the door to a closer level of cooperation outside the lodge than the groups had ever known.

Since then, Prince Hall and Grand Lodge of California Masons have stood side by side, proudly demonstrating the universality of Freemasonry.

These days, the fraternity is much changed from its halcyon era, but thanks to partnerships like that and the unbroken chain linking members today to those of the past, its history and legacy live on for generations of Masons to come.

Photography by:

Courtesy of the Royal E. Towns Collection, African American Museum and Library at Oakland

Courtesy of Denise Williams

From the Eastern Star to the Prince Hall Shrine, exploring the many appendant bodies of Prince Hall Masonry in California.

Across the state, California Masons are reaching out across lodge lines.

The most frequently asked questions about the historic branch of the fraternity.