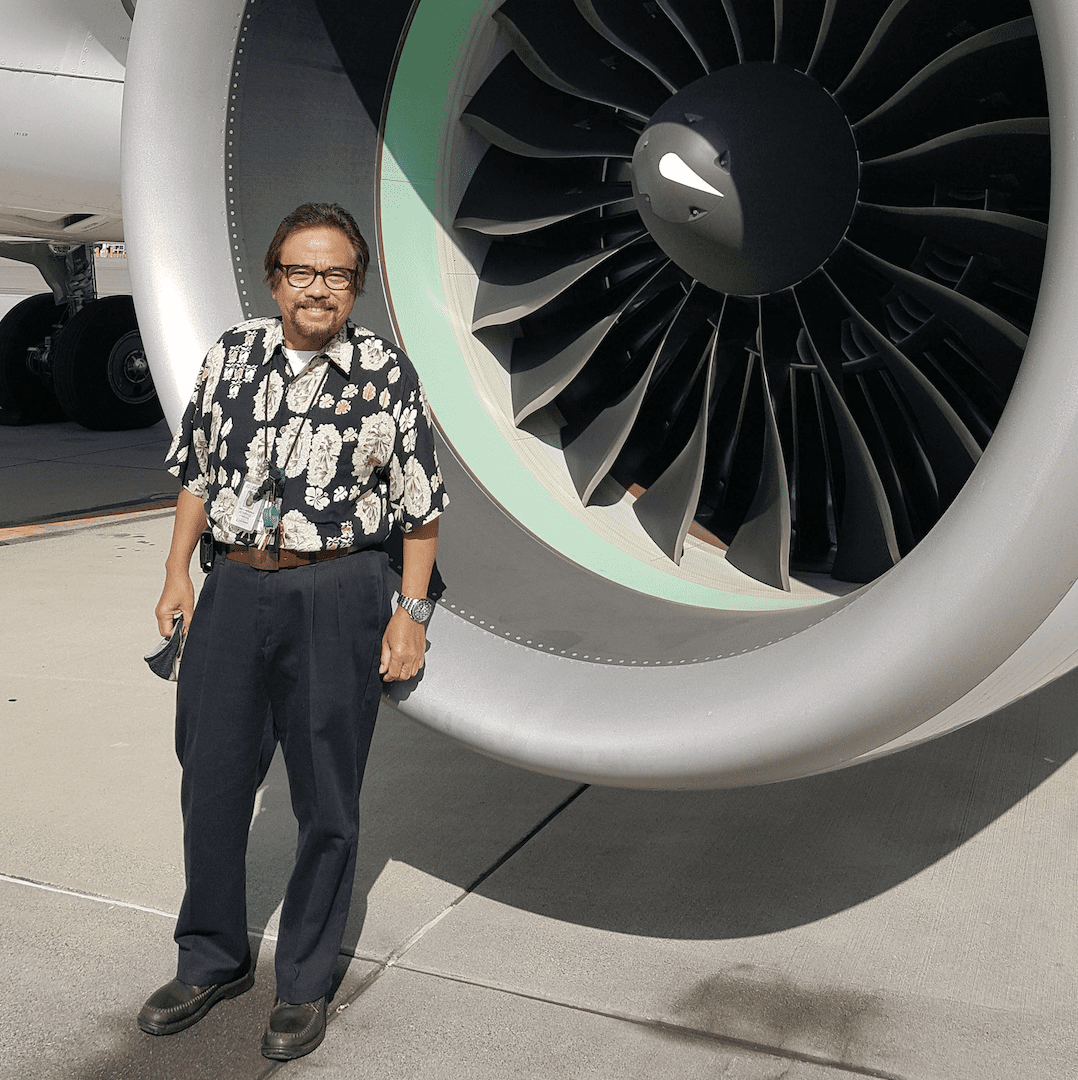

Donor Profile: Antonio Cimarra

An aviation expert, this SoCal Mason has seen Masonic relief up close. That’s why now, he makes a point of giving back.

Jared Murray didn’t talk to his daughter the night she died. But she had reached out to several people in the hours before she was fatally struck by a freight train in Sacramento. The 18-year-old called her mom; she called friends. Kendall even checked herself into a hospital emergency room, as her father had instructed her to do whenever she was having a breakdown. But doctors released her back onto the street. Officially, the medical examiner ruled Kendall’s death a suicide. Nobody knows if she was purposefully on the tracks, or if drugs caused her to lose awareness of where she was.

As a professional mortician, Murray is more familiar than most with death. But losing Kendall brought on a level of grief he’d never experienced before. He’d lived his entire life surrounded by reminders of the end—his father and brother both owned their own funeral homes. He remembers watching his father perform embalmings and plan funerals. At various points, the family had even lived in their funeral home. In fact, at the time of his daughter’s death, in 2019, Murray was closing a deal to purchase the Tracy Memorial Chapel, where today he works as a funeral director.

Murray, a Master Mason from Mount Oso № 460 in Tracy, had always considered himself an empathetic soul. But after Kendall died, he felt even more strongly that he’d been called to help others in his position. At a funeral home, every manifestation of loss is on display—fear, anger, frustration, indecisiveness. Now he regularly shares his story with clients, particularly those burying a child. “Helping them through the process helps me,” Murray says. “I don’t do it for praise or acknowledgement. I do it because I want to. This could be the worst day of a person’s life. If I can help them get through it, that’s the reward for me.”

That’s a familiar refrain among Mason morticians like Murray. While morticians come from all backgrounds, the common denominator is an ability to confront death and maintain composure.

Above:

Jared Murray of Mount Oso No. 460. As a funeral home owner, Murray relies on the skills he’s learned in Freemasonry to build empathy with the families he serves.

Perhaps it’s no wonder that among their ranks are a disproportionately high number of Freemasons. A rudimentary search reveals more than 75 members of the fraternity in California who are either Mason morticians, funeral directors, or related jobs. Masons understand the solemnity of ceremonial rites and have an appreciation for symbolism and allegory concerning death and mortality. That makes them especially well-suited to mortuary work, which requires a deep reservoir of empathy and compassion.

In Masonry, the goal is always to strive to do better, says Adrian Howard, a mortician at the Alpha Society funeral home in Burbank and a member of South Pasadena № 290. Masonry asks its practitioners to constantly reflect on the consequences of their actions, he says, and to recognize that life is about deepening relationships with the living. So too does his profession.

As a Mason mortician, he exemplifies those traits. Howard works every function of his funeral home: He calls doctor’s offices and files death certificates. He facilitates funeral services with priests. He arranges burials and cremations. He visits morgues and flower shops. He carries coffins. Occasionally, he texts family members weeks or months after a funeral just to let them know he cares. When someone dies and lacks family or anyone close to grieve their loss, Howard makes sure their life is still celebrated, as was the case when a 103-year-old woman who’d outlived her entire family passed away and came into his care. Howard arranged for 20 members of his staff to attend a funeral service in her honor. “Funerals are definitely for the living, but out of respect for the person’s life, when they pass, we should be there for them,” he says.

That’s especially true of Masonic funerals. Howard estimates that he’s attended at least 50 of those, many for brothers he never met in life. That kind of empathy is the stock-in-trade of the Mason mortician, he says. “The day you stop caring is the day you need to be out of this business.”

Bill Fischer has been an embalmer since 1984. The best part of his line of work, he says, is in showing extreme care for the deceased. Death is “a special time,” says Fischer, of Reading Trinity Lodge № 27. Fischer says he treats every person’s body as if it was a member of his own family. As general manager of Janus Advisor, which has 14 funeral homes in Northern California, he instructs his staff to always imagine the family of the deceased in the room watching their loved one being prepared for public viewing. Fischer says the job serves as a daily test of the ideals of Masonry: honesty, respect, and integrity.

Perhaps no lodge better exemplifies that connection than Pacific-Starr King № 136 in San Francisco. No fewer than five members there work in the funerary service, including German Lopez, a past master of the lodge, who recently retired after a 54-year career at Cypress Lawn Funeral Home in Colma. Lopez’s first exposure to the fraternity came through Masonic funerals he witnessed at the cemetery. Struck by the reverence with which members memorialized their deceased brothers, he soon inquired and applied for membership.

Another member of the lodge, Craig Willis, is a licensed embalmer who works on both people and pets. Like so many of his colleagues, it was through his funerary work that Willis connected with Freemasonry. One of Willis’s early mentors, Edward Sandmeier, was a member of Pacific-Starr King № 136, and after several conversations about the craft, invited Willis as a guest to a lodge dinner. “When you work in the same room for eight hours a day, you run out of things to talk about,” Sandmeier recalls. “Masonry came up, and when he asked about it, I told him, ‘You know, you can just come with me to my lodge.’”

And though he’s surrounded every day by the trappings of the hereafter, Willis says his experiences as both a mortician and a Mason have evolved his views on the here and now. “Working with dead people, you see death all the time, but you use it to be better.”

Or, as Fischer puts it, “It helps you appreciate that you have a life. You have today. Do the things you enjoy, and tell the people close to you that you love them.”

Murray didn’t get that chance the night his daughter died. But having his family take responsibility for preparing her body was, he says, a final act of love for her. He wouldn’t have had it any other way.

“My dad said the funeral industry was a calling and not a job,” he says. “There are people who can handle this industry and those who can’t. We have to be the strong person in the room. We have to take people by the hand and show them the steps.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY

Peter Prato

An aviation expert, this SoCal Mason has seen Masonic relief up close. That’s why now, he makes a point of giving back.

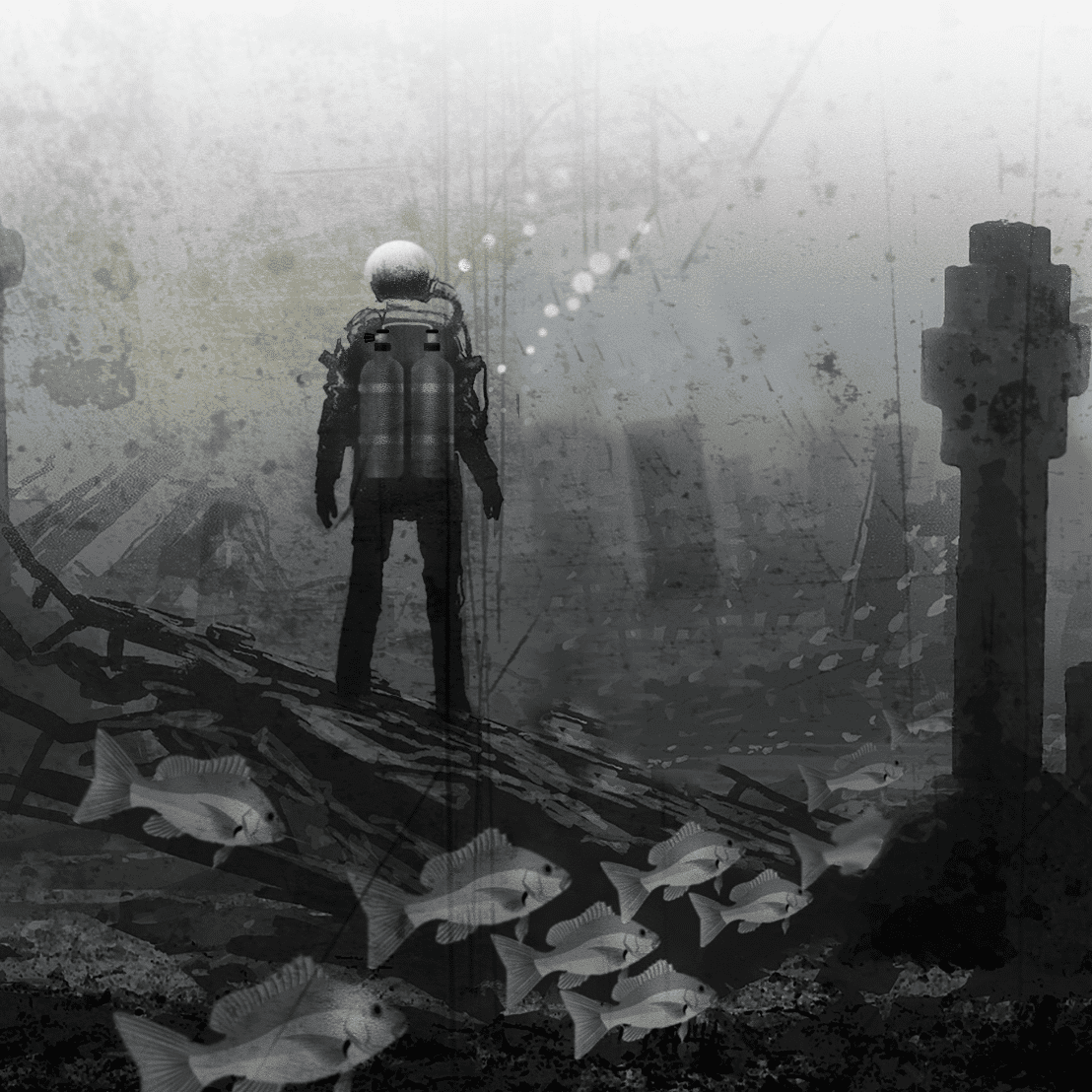

Buried among the rocks and rubble of San Francisco’s Aquatic Park breakwater, a reminder of a long-lost Masonic graveyard.

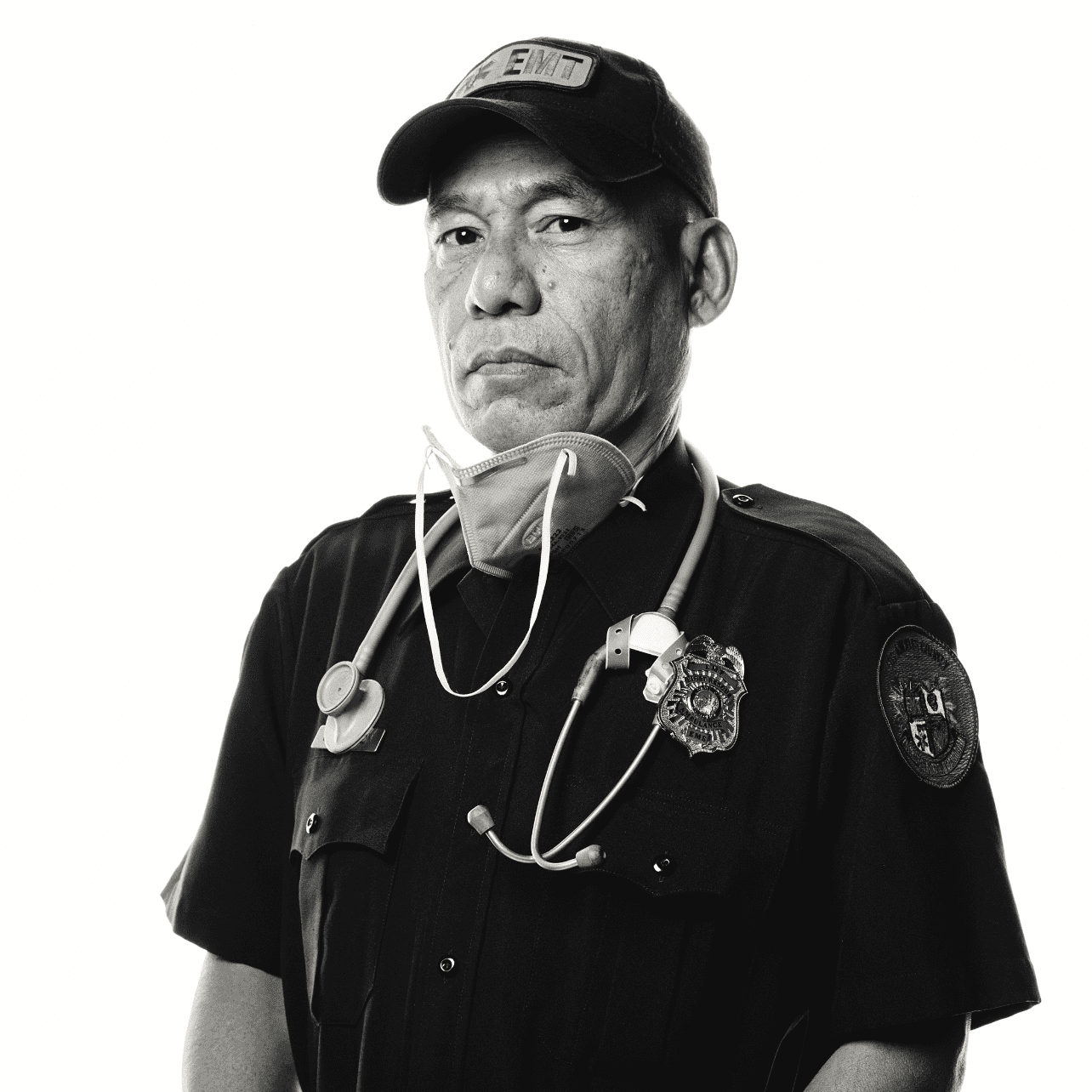

Meet three Masons with an intimate familiarity with death—and the other side.