For 2022, Masons4Mitts Returns with a Focus on More than the Mitt

Masons4Mitts returns for another season with the support of the Masons of California and the California Masonic Foundation.

Health care workers face death and dying on a daily basis. It’s an experience that can rub a man raw if he lets it, especially in the pandemic era. For Guillermo “Dondi” Manzon, an emergency medical technician and former officer for Sunnyside № 577, the philosophical teachings of Masonry are some of his most important tools for staying grounded.

Manzon, 58, didn’t originally set out to pursue his current line of work. When he immigrated from the Philippines in 2002, he had a degree in engineering and experience as a pharmaceutical rep. At first he found a job in marketing for a private ambulance company. But he was intrigued by ambulance work itself, and within a few years he gave up his job to start his next chapter. “Just like that I was an EMT,” he says. Well, not quite: There was training involved. “Lots of training,” he says with a laugh.

During his first shift, Manzon immediately had a brush with death. “We got a call for this man who was on dialysis; he was unresponsive,” Manzon says. On their way to the hospital, Manzon had an epiphany of sorts. “I remember staring at this man, who was only in his fifties, and thinking to myself, Wow, I need to lead a good life while I can.” It took him several more years to find Masonry, but when he did, it all clicked. “Here was a group of men who made it their mission to do good in the world,” he says. “I knew I wanted to be a part of this force for good right away.”

Although he had grown up around Masonry, with his uncle and other relatives in the Philippines belonging to lodges, Manzon had never really thought much about the fraternity until he began his second career.

Over the years, Manzon has clung to Masonic philosophy when times get tough. In a dozen years as an EMT, he’s never had a patient die on him, but he’s still seen more suffering than most people. “Freemasonry has helped me deal better with my ill patients,” he says. “It’s given me the tools to be a better man and look after people the best way I know how.” For Manzon, the most impactful tenet of Masonry is the one that charges a man to be an upright citizen. “That directly translates to my work,” he says. “I strive to be a better EMT every day because of it.”

In the end, Manzon knows there’s only so much he can do for the individuals that pass through his care. But with Masonry in mind, he has a framework to better handle the stress his work can entail. “Religion has taught me salvation after death,” Manzon says. “Freemasonry has taught me how to live.”

A musician and erstwhile gravedigger reflects on what we leave behind.

The first song Dylan Luster ever recorded was written after spending an uncommon amount of time among the dead. He was 25 years old, newly sober, and coming off stints as a gravedigger and crematorium worker. At the crematorium, his task was to crawl into the facility’s incinerators to sweep out the residual ash. The furnace was massive—and imposing—reaching temperatures of 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit. “The door was like 400 pounds of steel,” Luster recalls. “If the chain that was hoisting it up broke, there was no way to lift that thing. Sometimes I think about it—like, jeez, I was in some other mindset.”

The grisly work forced Luster to confront big questions about life and death. And it awakened his artistic spirit. In one of his first recorded songs, “Soul Remains,” he writes, “I been workin’ on my life, through the pain and the trouble and strife / They can break my body, but the soul remains.”

Years later, the indie-folk singer still finds inspiration in transience. Luster’s time at the crematorium was bookended by a groundskeeping gig at a cemetery near his childhood home in Norwalk. The work, quiet and contemplative, suited his temperament. While watering flower beds, mowing grass, and yes, digging graves, he let his mind wander. “Once I started to really sober up, I wanted to go back to the peaceful gardening at the cemetery,” he says.

That wasn’t Luster’s only inspiration. Around the same time he decided to get clean, Luster’s mother shared three blue books with him, inscribed with the words “NOVEMBER 6, 1933 INITIATED.” They contained the work The Symbolism of the Three Degrees by Oliver Day Street.

The books had belonged to Luster’s grandfather, who belonged to a Masonic lodge in Fort Worth, Texas. Though they’d never met, for Luster the books served as a channel through which his grandfather could offer him guidance from beyond the grave. Finding Masonry at that tumultuous time gave Luster something to work toward. In 2013, he applied to Golden Trowel Norwalk №. 273; the following year, he was raised to Master Mason. In 2019, he affiliated with Yucca Valley № 802.

Masonry helped Luster navigate sobriety and process his thoughts. “It can occupy your mind with different philosophical questions and different threads to pull,” he says. It also sharpened his thoughts on death. “When I think about the afterlife, I don’t think of some other dimension. I think whatever you do in this world, it impacts other people. That is kind of where your spirit goes.” That outlook in turn helped Luster focus on his music career. In 2016, he released a self-titled EP. Last year, he put out two more singles, “Judy’s Highway” and “Eastward Winds.” Both explore those themes of impermanence—a common refrain in Luster’s work.

These days, Luster has a collection of 10 new songs in the works, grouped loosely on the experience of waiting for something to pass. Each song features instruments played and carefully recorded, one track at a time, by the musician. One of the tunes, “Other Side” could be about achieving a goal—like the completion of an album, or completing the degrees—or reaching the other side of this existence. He’s leaving it up to the listener to decide.

Though his official title on the television series My Ghost Story on A&E’s Biography Channel was casting producer, it’d be more accurate to call Chris Sanders a paranormal consultant. His work on the show entailed things like scouting haunted houses, sourcing esoteric experts, and vetting real-life ghost stories.

The gig was just one of many to showcase Sanders’ unusual expertise. And in the years since, he’s carved out a special niche for himself at the intersection of esotericism, metaphysics, and Hollywood. “I knew where to look,” Sanders says of his foray into what one might call supernatural television programming. “I knew how to speak the language of these folks.”

Sanders has had a lifelong interest in “the arcane and metaphysical.” In 1999, newly single, he moved to Los Angeles in search of something new. A chance encounter led him to a Hare Krishna temple, right around the corner from Culver City Foshay № 467. He decided to take a leap of faith. “It was a magical moment,” he says of approaching the lodge. “My prayers were answered. That sent me out on a whole new path.”

Sanders connected immediately to the philosophical aspects of Freemasonry, and within a year had been raised as a Master Mason and was serving as a lodge officer. In 2008, he became lodge master.

His personal interests have also opened some unlikely doors in Hollywood. While Sanders has had small acting roles in blockbusters like Pirates of the Caribbean: At the World’s End, Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland, and HBO’s True Blood, he’s also built himself into an on-screen authority on Freemasonry. In 2009, he was featured as an expert speaker in the History Channel show The Nostradamus Effect, as he was in the 2017 documentary 33 & Beyond: The Royal Art of Freemasonry. In addition, he’s served as a producer on the WeTV series Ghosts in the Hood, performed an exorcism on the 2013 A&E series American Haunting, and appeared as an actor and producer in several cult and horror films.

His entrée came from a suitably unlikely source: A couple of well-known witches who ran an occult shop that Sanders frequented. Having been approached by a TV producer, the shop owners recommended that Sanders be involved in a proposed reality series— which eventually became My Ghost Story: Caught on Camera. “They knew I had a background in the paranormal and was good on camera,” he says.

In February of 2020, Sanders landed his dream gig: a “fly-on-the-wall show” for a major cable network, shot from the barstools of the Little A’Le’Inn, a watering hole near Area 51 in Nevada. “You walk into this strange bar, you’re at the counter grabbing a beer, and the guy next to you is like, ‘I was abducted by Bigfoot,’” he explains of the show’s premise. “And you’re like, ‘Well, I was abducted by aliens.’”

Those are actual stories that would have been featured on the show—if not for COVID-19. Still in early production when the pandemic hit, the project was shelved.

It’s unlikely that project will be raised from the dead, but in the meantime, Sanders isn’t waiting around. Now, he says, his next project will be a memoir. “I thought, What do I have to offer this world?” he says. “The people I’ve met, the things I’ve seen and done. I have these stories in me. And they should be told.”

PHOTOGRAPHY BY

Russ Hennings/Moonbeam Studios

Luster photo courtesy of the subject.

Masons4Mitts returns for another season with the support of the Masons of California and the California Masonic Foundation.

It takes a special temperament to succeed as a mortician—and one, it turns out, that Freemasons are well suited to.

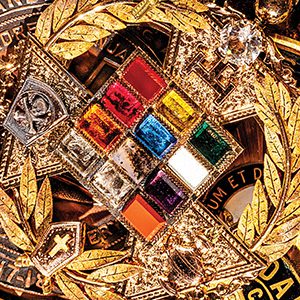

To some, collecting Masonic artifacts, rings, aprons, and jewelry isn’t just a hobby. It’s a craze.