At a Masonic Cemetery, a Forever Home

In rural Tuolumne County, a new effort to bring a pair of Gold Rush era Masonic cemeteries back to life.

The way Tigran Agadzhanyan tells it, he didn’t find the 14-karat gold Masonic officer’s jewel. It found him. The two came together a few years ago at a shop where Agadzhanyan was having an old Masonic ring resized. The shop owner recognized the insignia and said that he had a special piece that Agadzhanyan needed to see. Out came the circa-1886 Grand Royal Arch medal, housed in a handsome red box. “He said he’d been holding on to the piece for 30 years trying to find the right home for it,” Agadzhanyan says. Little did the jeweler know, in Agadzhanyan he’d found the perfect home for the Masonic artifact.

Only 25 years old, Agadzhanyan, of Live Oak № 61 and Oakland Durant Rockridge № 188, is already one of the state’s most enthusiastic collectors of Masonic artifacts, jewelry, and regalia. More than 800 Masonic artifacts are stored in his East Bay home, in museum-grade archival boxes and acid-free preservation sleeves, from officer’s pins to tracing boards. In his free time, Agadzhanyan, a graduate student in government at Harvard (he’s taking classes remotely), can be found trawling eBay or flea markets for fraternal keepsakes.

Agadzhanyan recounts some of his antique hunts with the zeal of an obsessive. “I’ve definitely been called crazy,” he admits. Once, at an antiques warehouse in Monterey, he recalls feeling “something cosmic. It’s like there’s something here and I have to rescue it.” Sure enough, he spotted a pair of Masonic certificates from the early 1900s to add to his collection.

Above:

Tigran Agadzhanyan flanked by Masonic certificates, tracing boards, and other mementos, inside Oakland Durant Rockridge Lodge № 188.

That feeling is common in serious collectors, says Heather Calloway. Calloway is the former managing director at the Scottish Rite Museum in Washington, D.C., and now executive director of university collections at the Center for Fraternal Collections and Research at Indiana University. “People find them fascinating,” she says of Masonic artifacts.“They tell the story of American history, of American life.”

However, for all their historical significance, it’s rare for major museums and archives to collect fraternal mementos. Only a few institutions, including the Grand Lodge of California, have a professionally managed repository. “So basically, you have people who are really passionate about these organizations who are collecting so their history doesn’t disappear.”

Agadzhanyan’s first exposure to the that history came at UC Berkeley, where he would often walk by the former lodge hall of Durant № 268. He eventually joined the consolidated Oakland Durant Rockridge № 188 and became involved in helping sort through the lodge’s archives. Fascinated by the old memorabilia, he began searching online for pieces associated with the lodge. That led him to an apron from the 1920s that had been owned by a past member of the lodge. With that, Agadzhanyan’s collection was off and running.

Today, he counts among his most impressive pieces a Royal Arch pendant from 1857 and an officer’s jewel from 1840. But often it’s the pieces with a personal connection that are his most prized. In that vein, he points to the Scottish Rite certificate he inherited from his late mentor, Albert Keshishian. “They’re not necessarily for me,” he says. “They’re for something bigger, to preserve our fraternity’s history.”

Adam Kendall hears similar sentiments all the time. Kendall is the executive director of the Oakland Scottish Rite Historical Foundation, where he’s helping build out its archive and museum. That often means sifting through dozens of pieces, trying to spot the ones with interesting histories. Recently, he says, he was able to find and purchase a trinket with just such a story. The item is a small pin featuring a winged heart on one side and a bird set within a compass on the other. The pins were worn for an 1893 burial presided over by Edwin Sherman, the founding father of the Scottish Rite on the West Coast. The service was in memory of Jose Ignacio Herrera y Cairo, a former governor of Jalisco, Mexico. Herrera was killed during the Mexican Revolution. But before his death, he asked that his heart be preserved to show he’d died for his devotion to Masonic principles.

Years later, Herrera’s sister transported the mummified organ to Oakland to be interred at Mountain View Cemetery. Thousands of Masons wearing the custom-made pins escorted his remains to the gravesite.

So when Kendall saw one of the pins for sale on eBay for $50, he jumped on it.

Like Agadzhanyan, Kendall speaks of his collecting as more of an obligation than a hobby. “I’ve never refused even a plain white apron,” he says. “My fear is, What if it’s important?”

That’s how Agadzhanyan felt when he first saw the Royal Arch medal at the shop. Although it was out of his usual price range, he was compelled to take it home. “If I didn’t buy it, someone was going to buy it and melt it down,” he says. “It was for the greater good.”

PHOTOGRAPHY BY

Winni Wintermeyer

In rural Tuolumne County, a new effort to bring a pair of Gold Rush era Masonic cemeteries back to life.

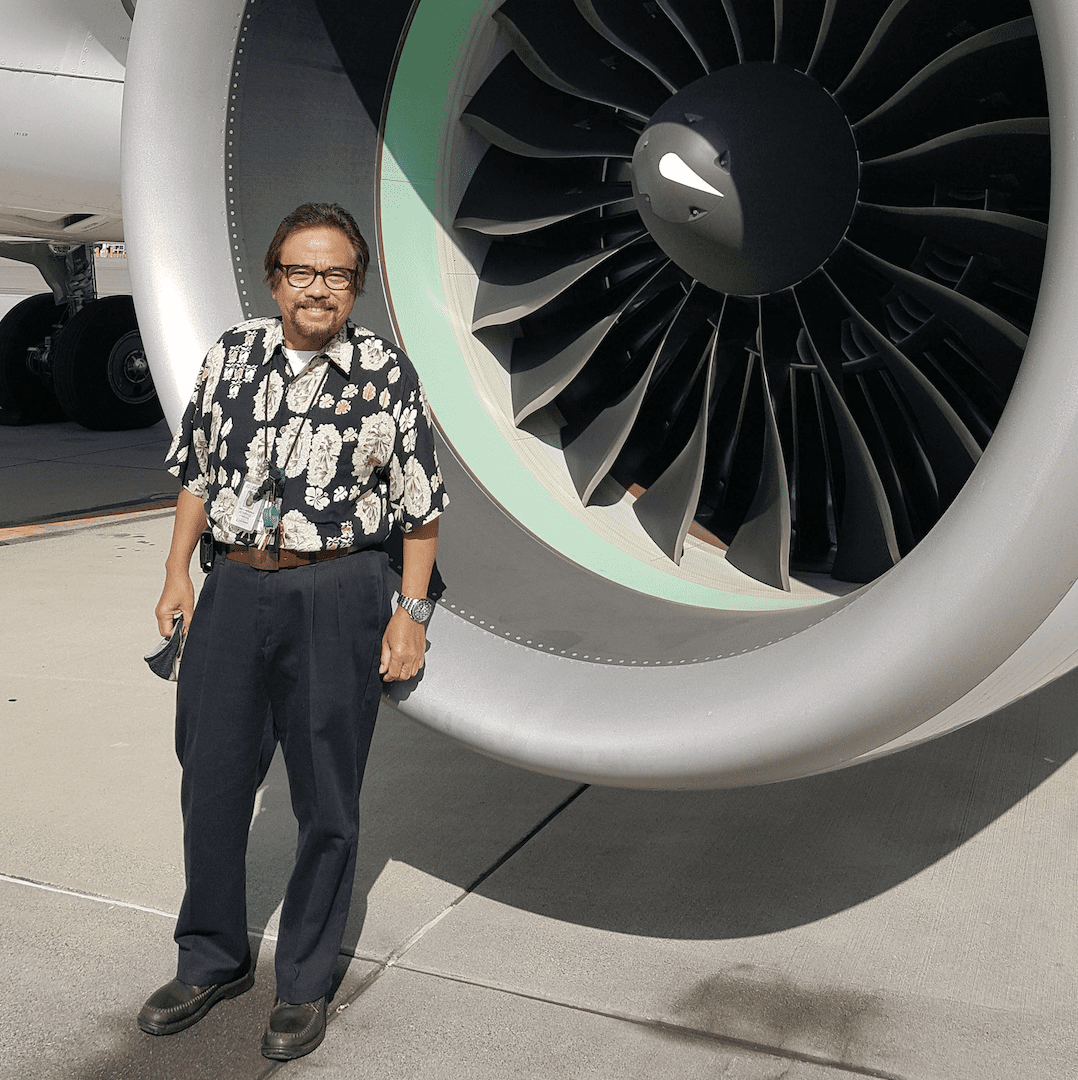

An aviation expert, this SoCal Mason has seen Masonic relief up close. That’s why now, he makes a point of giving back.

Thanks to lodge volunteers, Masonic Outreach Services can be everywhere to provide support to those in need.