Lodge Profile: The Do-It-Yourself Lodge

For members of San Francisco’s Logos Lodge No. 861, creativity permeates all aspects of lodge life.

By K.M. Soehnlein

What does an old officer’s apron tell us about our state’s history? What can lodge banners say about the fraternity’s relationship to the wider culture? These are the kinds of questions driving a new exhibition, From the Hands of Fellowship: Masonic Folk Art from the Collection of the Henry W. Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry, launching during Annual Communication at Grand Lodge in San Francisco Oct. 18–21.

Organized by Museum Collections Manager Joe Evans, From the Hands of Fellowship celebrates handmade fraternal objects including aprons, quilts, walking sticks, and more, mostly dated pre-1850. Contained within these pieces are larger clues about their owners, their community, even gender and class distinctions.

From the Hands of Fellowship will remain on display throughout 2019 by appointment. Here, Evans goes deep on a few of these beautiful, mysterious relics.

circa 1800–1807

Watercolor and ink on silk, linen

20″ x 17 1/4″ | Acc# 79.12

Most 19th century Masonic aprons don’t indicate who their owner was, however this one bears an inscription under the flap: “Brother Ralph Hankins, Tammany Lodge No. 83, November 16, 1807,” a lodge near Milanville, Penn. Hand-painted in watercolors, this silk and linen apron employs a German folk style that shows up in the handcrafts of immigrant communities along the Mohawk River in Pennsylvania and New York. The female figure personifying Hope, with her characteristic anchor, stands in profile at the center. Donated in 1978 by Jean A. Laipple of San Francisco.

circa 1850–1900

Wood and bone

3″x 6″x 2 1/2″ | Acc# 2002.2

This rare, small wooden box replicates a lodge room in miniature, though its story beyond that remains a mystery. It conceivably served as a map or blueprint for candidates, or as a way for lodge officers to practice floor work. The box and its checkerboard interior date from the mid-to-late 19th century, while the miniature working tools inside the lid, carved from wood and bone, seem to have been added in the 20th century.

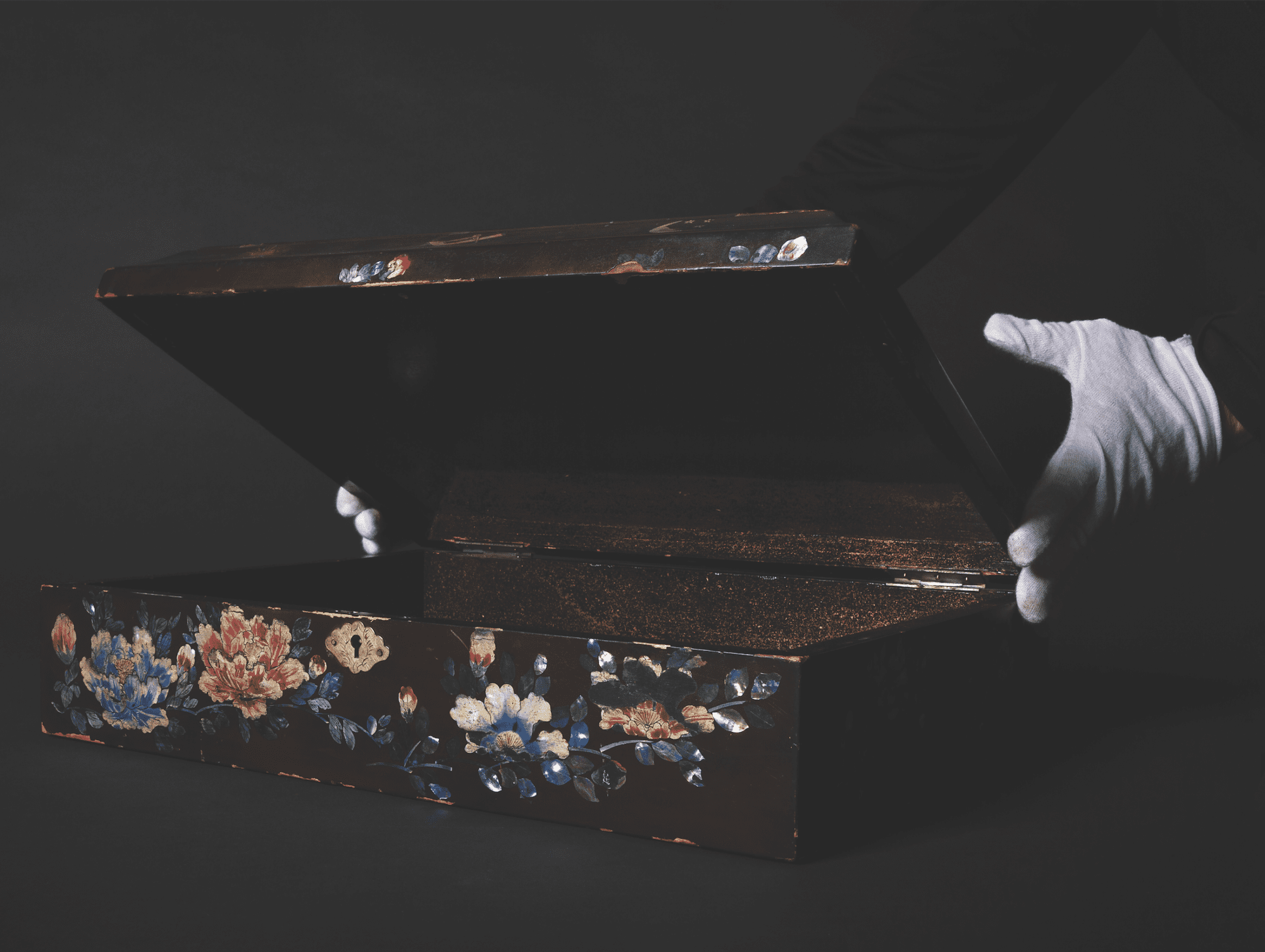

circa 1830–1850

Lacquerware, nacre

5″ x 16 1/2″ x 12 1/2″ | Acc# 2013.1.1

Originating in Japan in the middle of the 19th century, this beautiful black lacquered keepsake box is decorated with mother-of-pearl inlayed floral designs and Masonic symbols: the all-seeing eye, altar, beehive, hourglass, compasses, square, clasped hands, and trowel. Since Freemasonry did not exist in Japan during this period, Japanese craftsmen probably produced boxes like this one for a sea captain or to be traded in Europe.

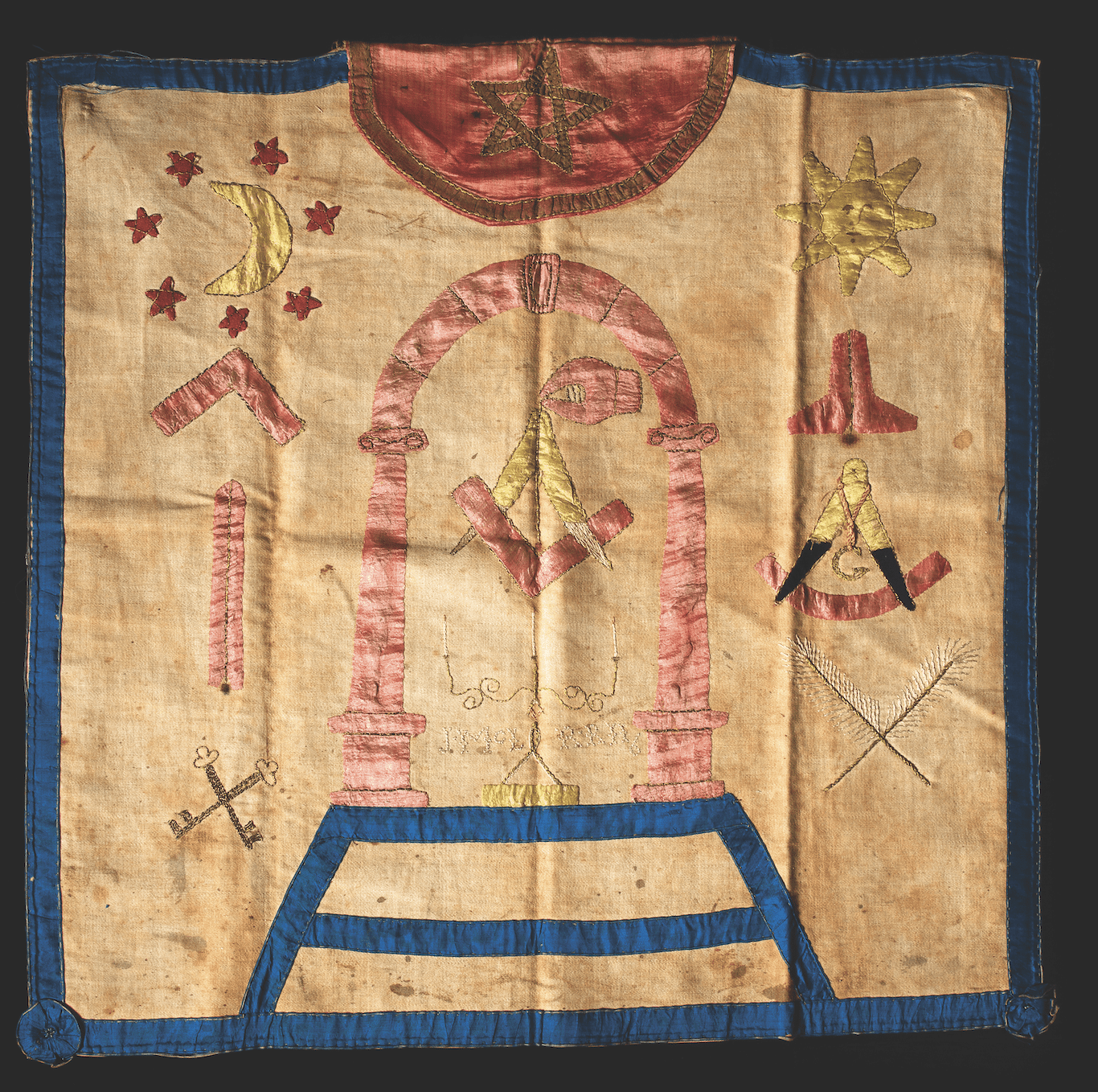

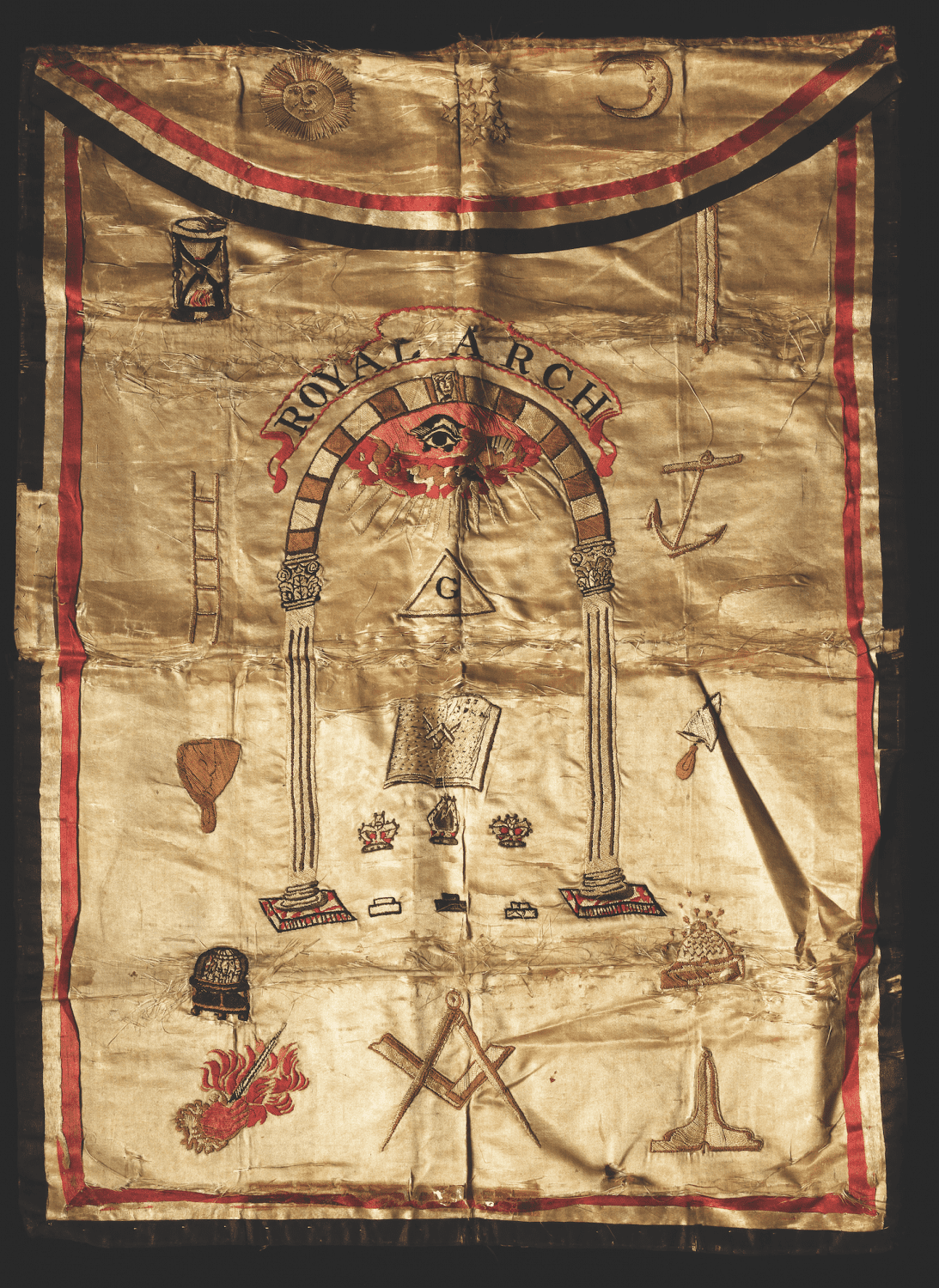

circa 1830–1850

Silk, hemp linen, cotton

23 1/2″ x 24″ | Acc# 2007.3.1

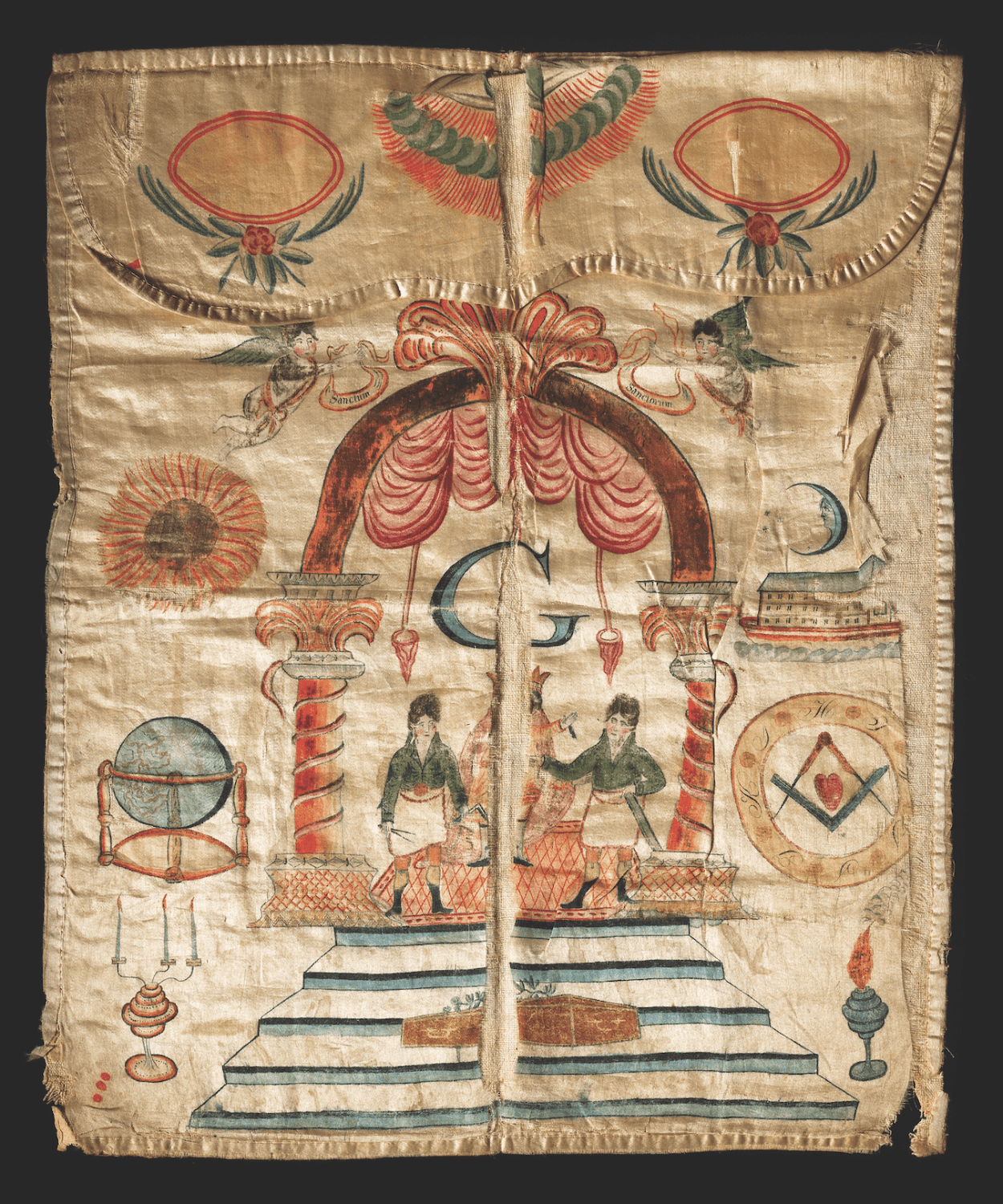

circa 1800–1820

Watercolor and ink on silk, linen

21″ x 17 1/4″| Acc# 396.1

circa 1820-1840

Silk, cotton

25″ x 18″ | Acc# 2019.2.1

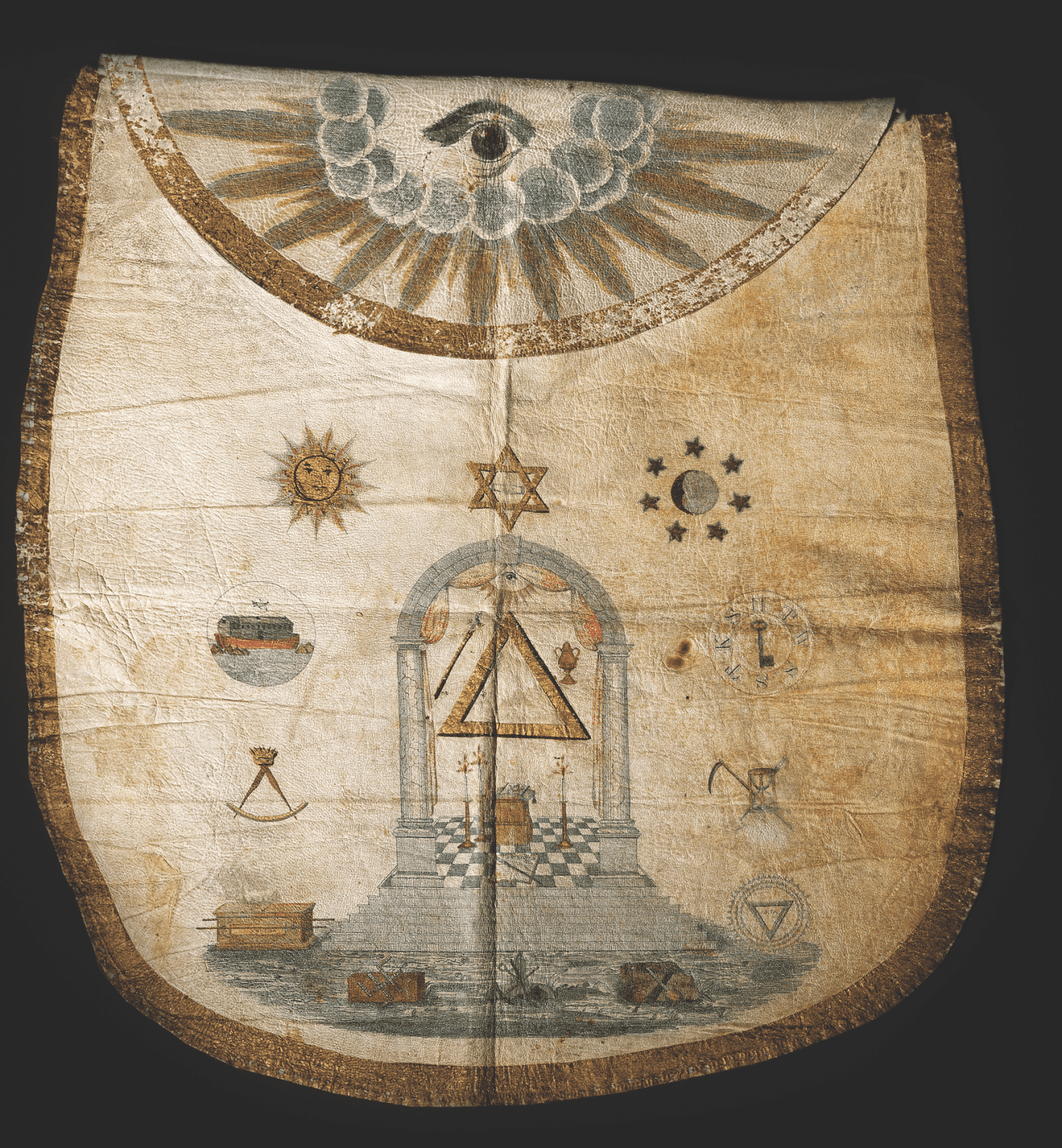

circa 1800–1820

Paint and ink on leather

14″ x 13″ | Acc# 284.1

The Royal Arch symbol anchors many of the aprons found in the Masonic archive, including many pieces donated by Leslie Woodworth, a prominent collector of Masonic memorabilia (C). Figure B is of unknown origin but closely resembles aprons made by folk artist Conrad Edick held in the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library in Lexington, Mass. Edick worked in 19th century German immigrant communities in Pennsylvania and New York. Another piece, (A), a Scottish apron of hemp linen, is unusually large, mimicking the workman’s aprons worn by operative stone masons of the mid-19th century. Designs for aprons in the early 1800s were often copied by engravers from books, after which professional painters would add artistic touches such as gilding, as seen on apron D.

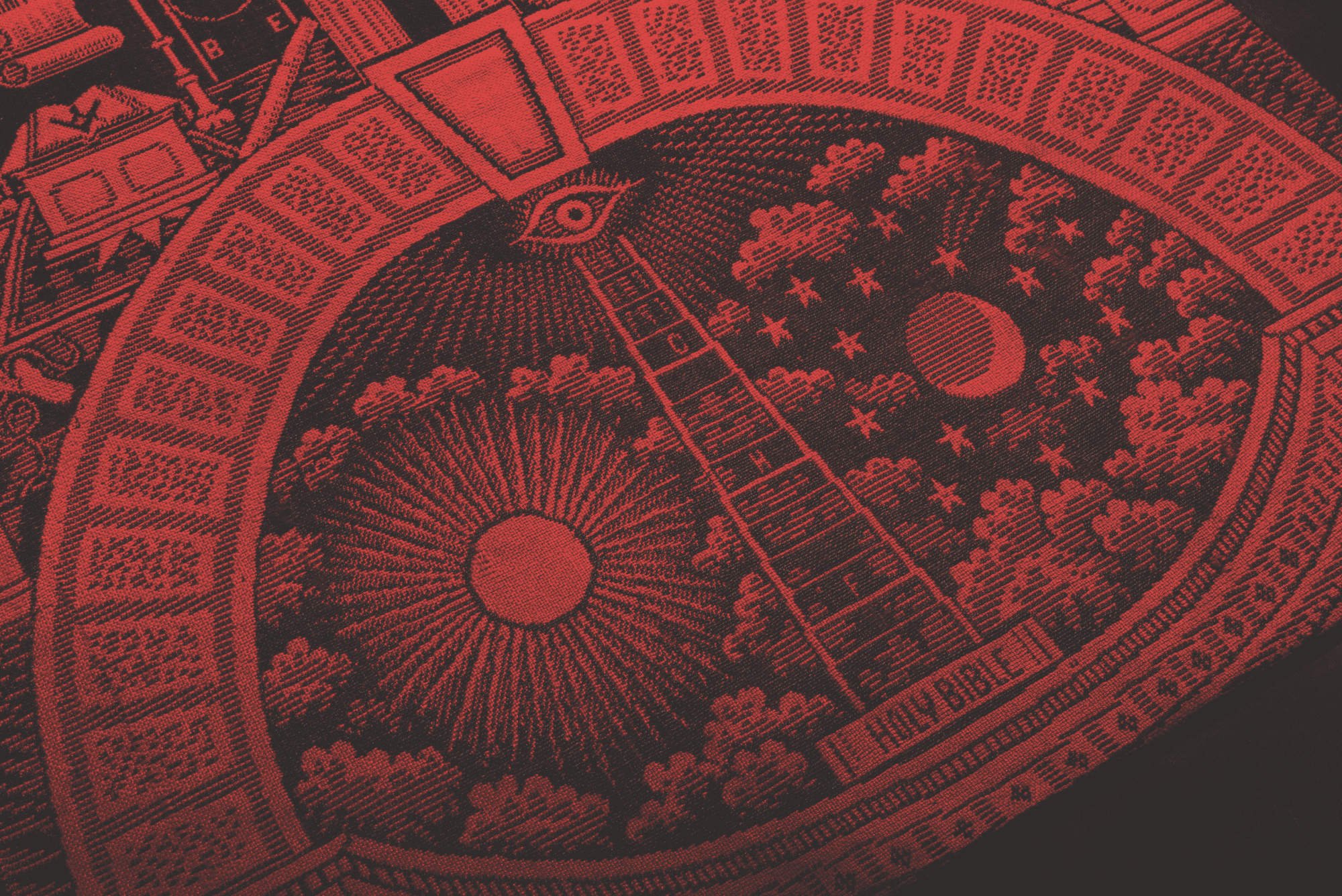

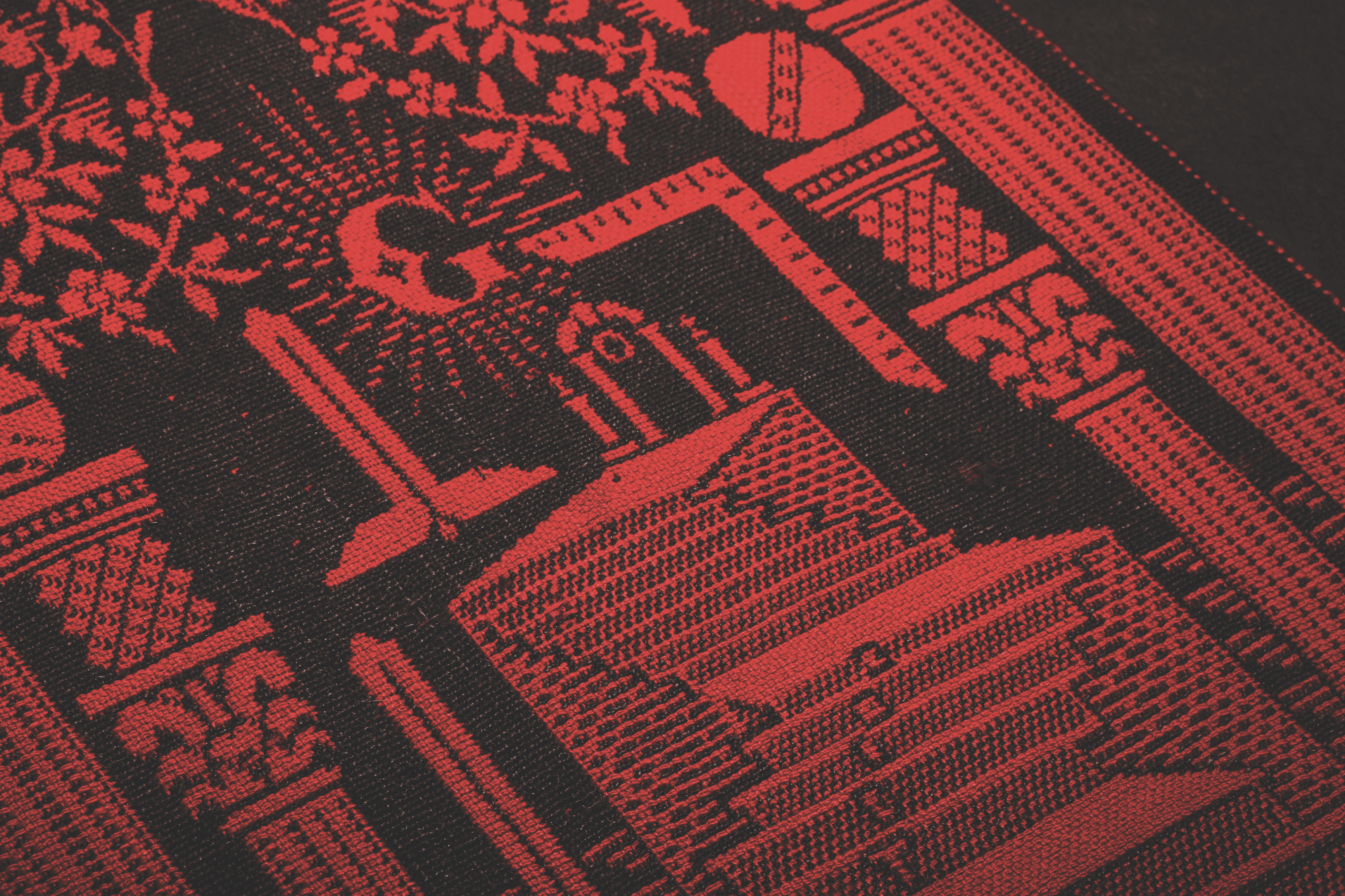

circa 1860s

Wool

87″ x 36″ | Acc# 24

This bold, red-and-black carpet fragment may have been woven by the Sisters of the Order of Holy Cross at St. Mary’s College, South Bend, Ind. The carpet’s pattern repeats a tiered series of arches. An individual segment like this would have been sewn together with others to create a large area rug. Apparently, this piece of the carpet was used as tapestry after Esmeralda Lodge No. 6 became part of the Grand Lodge of Nevada in 1863.

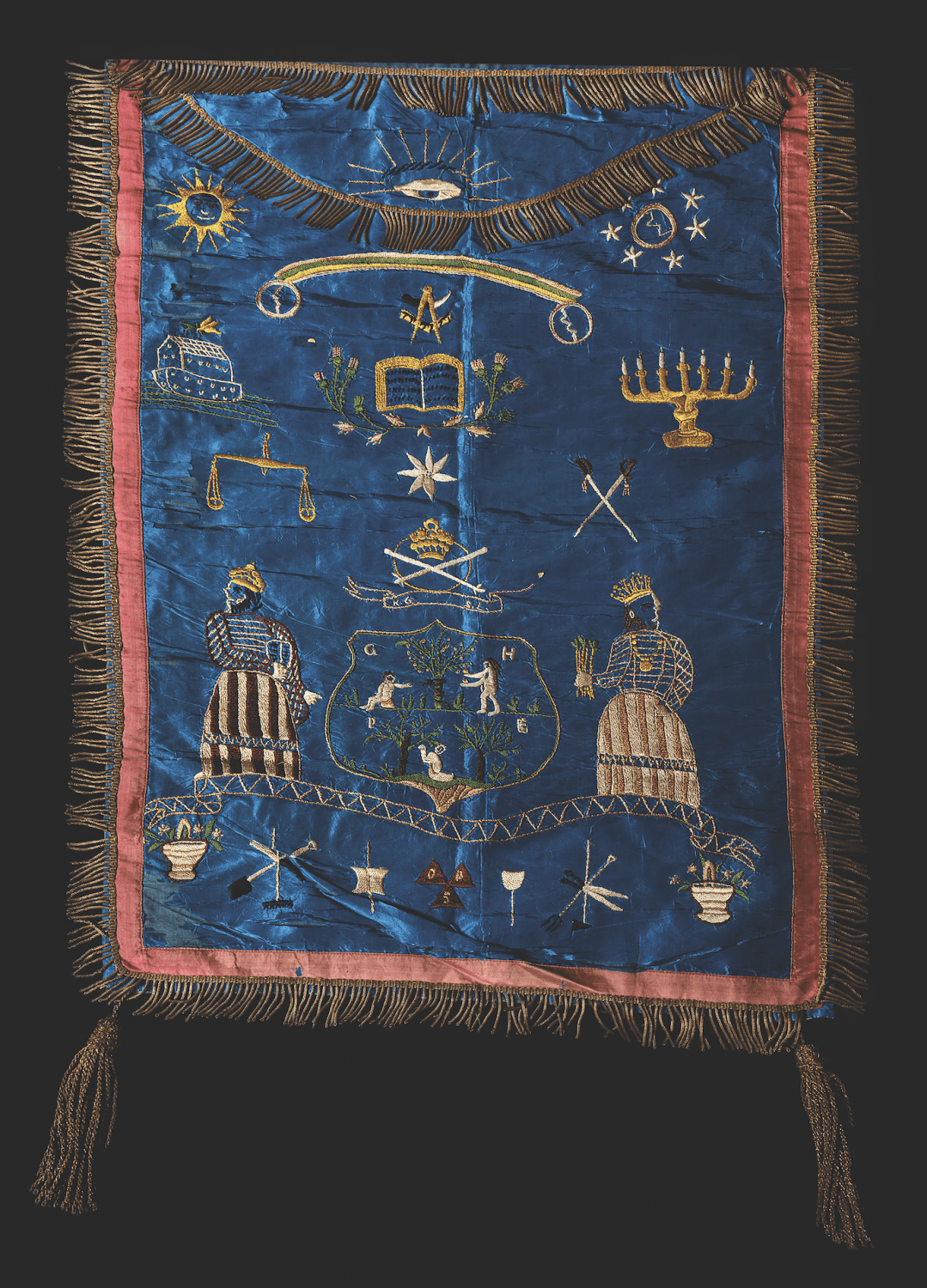

circa 1840

Silk, cotton

31″ x 20″ | Acc# 2019.1.1

Not quite Masonic, this dramatic, oversized blue silk apron has its origins in the Free Gardeners Society, founded in Scotland in the 17th century to promote and regulate the gardening profession. The society, which spread to England and eventually the United States, resembled Freemasonry in its lodges, lodge officers, and Grand Lodge. During the 19th century, the Free Gardeners adopted many symbols of Freemasonry including the square, compass, and grafting knife. The initials A, N, and S (in the triangles at the bottom) represented the biblical figures Adam, Noah, and Solomon, all claimed by the society as master gardeners.

circa 1900

Wood, brass, bone

4 1/2″ x 2 1/2″ x 1 1/2″ | Acc# 90.36A

Found in an antique shop in Paris, this curious, handmade wooden box, with its precise brass fittings, seems to be of Masonic origin. The central figure, carved in bone, activates the box’s lock when pressed. The seven brass symbols mounted on the front (U, V, C, T, square, compass, hammer, ax, pinchers, awl, and planer) allude to a fraternal organization such as the Compagnons du Devoir, comprised of French craftsmen and artisans dating back to the Middle Ages.

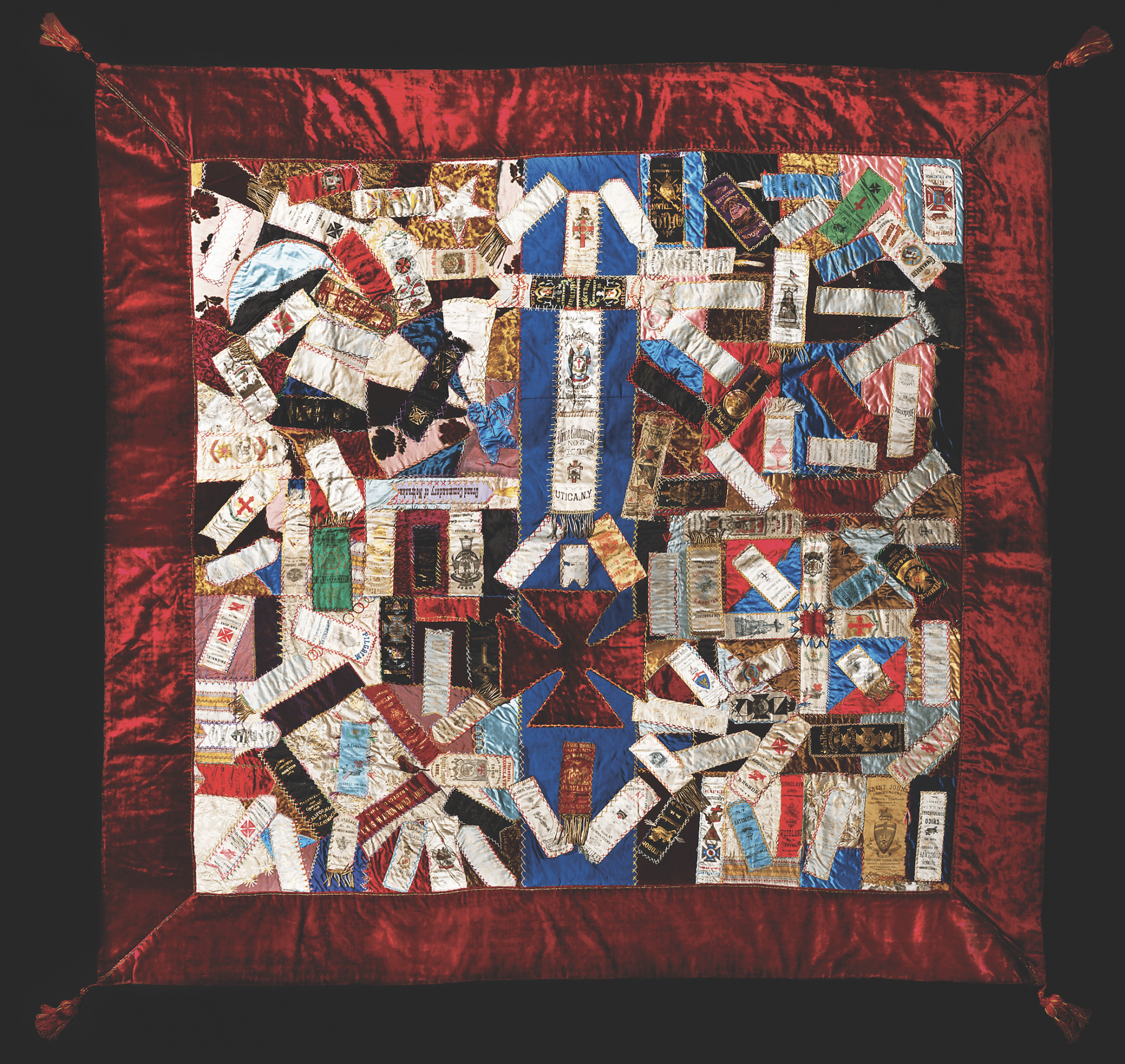

circa 1883–1900

Wool, silk, satin, cotton

70 1/2″ x 72 1/2″ | Acc# 2019.3.1

This intricate example of a “crazy quilt” would have been considered a status symbol in the late 19th century, a sign that its female quilters had enough leisure time and wealth to painstakingly sew it together. This one is composed of 115 ribbons from the 1883 Knights Templar Triennial held in San Francisco. The silk ribbons from the various commanderies that participated in the conclave, souvenirs of the event, became collectors’ items for spectators and participants. Not quite large enough for a bed, this was likely used as a sofa throw blanket or a piano cover.

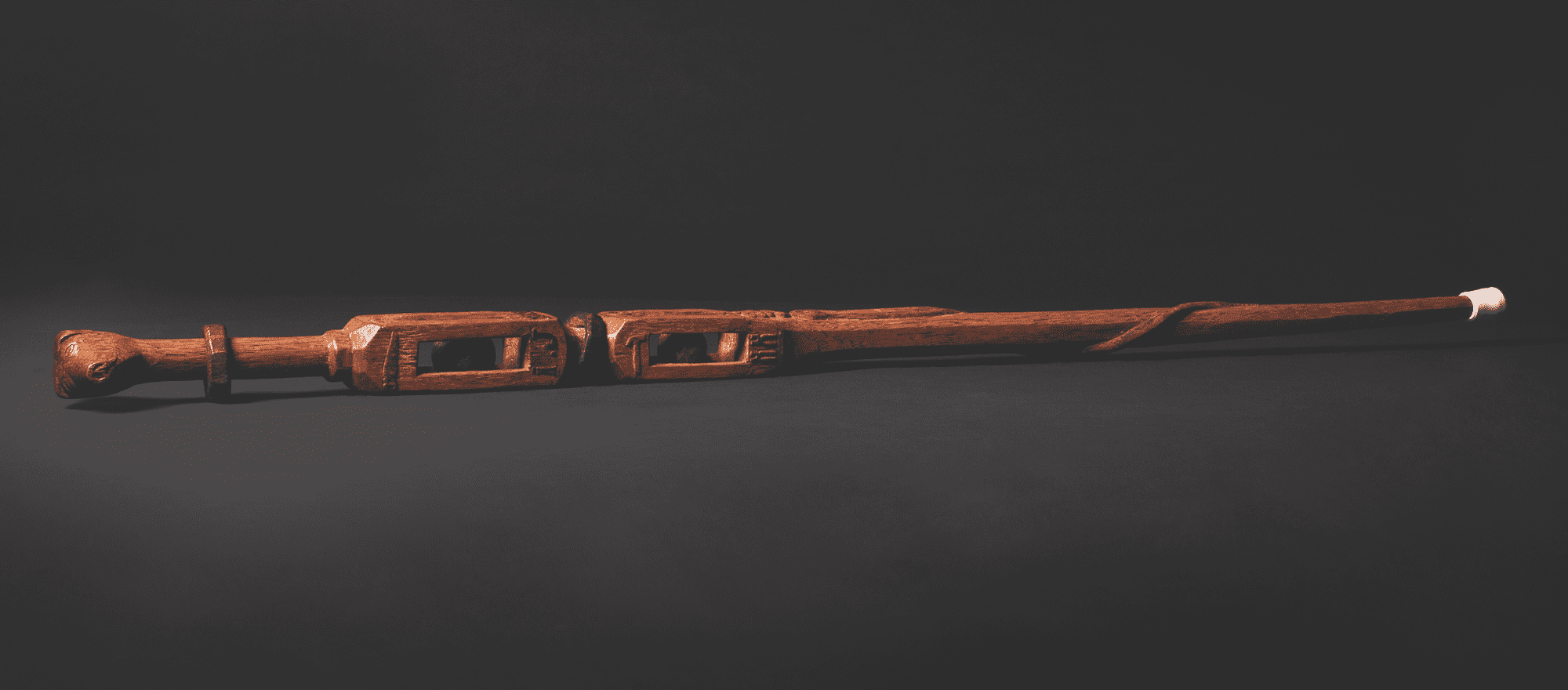

1897

Wood

37″ x 3″ | Acc# 99.7 23

The two-ball cane—with its with its enclosed, rolling balls—has been a popular Masonic folk art motif for over a century, honoring the biblical blacksmith Tubal Cain. This well-preserved example was hand-carved in 1897 by Ianthis Jerome Rolf, Past Master of Nevada Lodge No. 13 from 1875–77. Along with familiar Masonic symbols (compass and square) and wood carved animals (snake, frog, double-headed dog), Past Master Rolf carved his name and the date along the bottom of the cage, below the cane’s head.

circa 1820–1850

Watercolor on silk

16″ x 16″ | Acc# 86.3

The exquisitely detailed handiwork of this early 19th century apron— constructed of silk fabric and trimmed with a pleated red silk ribbon—includes, on the reverse, a basting stitch that fastens the muslin backing to the painted silk front. A more careful, barely perceptible running stitch is used on the front to finish the pleated ribbon, indicating that its maker, likely the wife or a female relative of its owner, was a highly skilled needleworker. Donated by Richard Shadburne of Goleta, whose grandfather, Ludwell McKay of Louisville, Kentucky, was the original owner.

PHOTO CREDIT: Kenneth Jong

For members of San Francisco’s Logos Lodge No. 861, creativity permeates all aspects of lodge life.

Folk art has long provided Masons with a creative outlet through which they can share their craft, inspire pride, and provide joy, says Junior Grand Warden Jeff Wilkins.

How do you tell a life story, set new goals, and define your legacy—all on a single lapel pin?