Creating a Culture That Unites

Junior Grand Warden Arthur H. Weiss explains the beauty and significance of Masonic material culture.

By Joe Evans

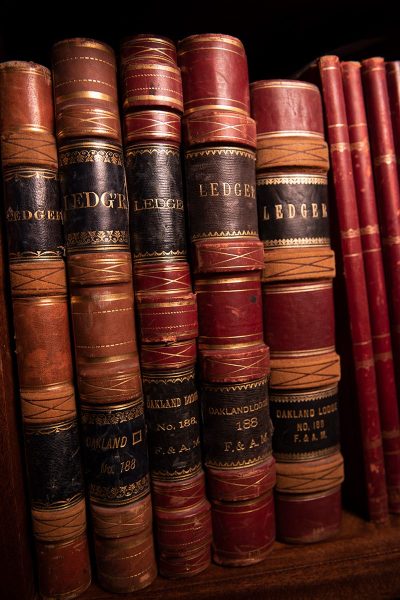

Lodges accumulate a mountain of records over the years, in the form of papers, books, artifacts, and photos. The sheer volume can get overwhelming.

Use these guidelines and tools to get rid of the clutter, and to take proper care of your lodge’s important records.

Permanent records

Keep these five essential records permanently:

Consult the Retention Schedule in the Member Center for a comprehensive list of what to keep, what to toss, and when. This document includes helpful reminders, such as when items should be added to an individual membership record, and notes when to discard common records – for example, financial statements, paid bills, invoices, and vouchers should all be discarded after 7 years.

Historical records

Other historical records should also be preserved permanently. These include:

Create an inventory with the Member Center’s Lodge Inventory Tool, which provides a simple way to keep track of items. You’ll list all items with a brief description, noting the location of the item and who made the inventory.

Basic preservation tips

Use these basic tips to store items properly. Review the Preservation Guidelines for Objects and Paper Archives, below for detailed instructions.

For questions regarding your lodge’s archives, contact Joe Evans, collections manager of the Henry W. Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry.

Most lodges maintain collections of paper records and some objects. Managing these objects and keeping track of them requires some basic practices to ensure their preservation. The following guidelines are intended as a brief introduction to the preservation of historic artifacts. It should not be considered a comprehensive preservation manual, but rather an introductory guide to basic, general preservation principles.

Most historic materials consist of two basic categories of materials – organic and inorganic.

Handling Historic Artifacts

In general, you should handle artifacts as little as possible. The oils, acids, and salts in human skin will damage most all types of materials over time. Whenever it is necessary to touch an artifact – for example, when setting up or taking down an exhibit or when re-housing the artifact for storage – use clean, dry, lotion-free hands. Or more preferably, wear clean cotton or latex gloves. Follow common sense, though, and do not wear gloves if the object could easily slip from gloved hands. Remove watches, rings, and other jewelry that might snag, scratch or chip the surface of the artifact. Also be aware of belt buckles, buttons, and other accessories that may come in contact with the artifact.

Ideally, artifacts should be handled and/or moved one at a time. Do not stack items in order to move them. In the case of very small, light artifacts, you may place them in a well-padded basket or tray, but do not allow the artifacts to touch. Do not try to carry large, bulky, or heavy objects by yourself. Always pick up an artifact – never push, pull or slide it. Use both hands and provide full support to the entire object, especially the base.

Before moving any artifact, make sure you have a clear place to set it. The workspace should be clean and free of food, beverages, and sharp instruments, such as pens, tools, paper clips, and keys. If possible, lightly pad the work surface (with archival quality materials) to reduce the risk of objects sliding or rolling off.

Environment

The major environmental factors that affect the long-term preservation of artifacts and paper are light, temperature, humidity, air pollution, and pests. The following guidelines are intended as a brief introduction to the preservation of historic artifacts. This should not be considered a comprehensive preservation manual, but rather an introductory guide to basic, general preservation principles.

Light

There are three types of light: ultraviolet (UV) light, infrared radiation, and visible light. All three types are harmful to artifacts and the damage caused by all light is cumulative and irreversible. In fact, displaying an object under ideal museum lighting conditions for just a few weeks could have the same effects as exposing it to bright sunlight for a day or two. You can take several steps to reduce the harmful effects of light. Because UV light is the most harmful type of light, make every effort to exclude or filter UV sources. The most common sources of UV are natural daylight and fluorescent lamps. Sources of natural light should be eliminated from all display and storage areas when possible, or filtered when elimination is not possible. Cover windows with shades, drapes, or blinds. Film products and Plexiglas-type sheeting are other UV filtering options. Even visible light can damage your artifacts. Reduce the harmful effects of visible light by simply turning off the lights as much as possible. Keep storage areas completely dark except for when retrieving or working with an artifact.

If items in the lodge rooms are on display, you may reduce the harmful effects of light on objects by rotating the artifacts on display. Return sensitive objects to storage after three months; less sensitive artifacts can be displayed longer, but periodically return them to storage for “rest.”

Temperature and Humidity

Maintaining a steady environment for artifacts is one of the most important ways of preserving your historical material. Fluctuation of temperature and humidity is what causes the most damage to objects and artifacts. The temperature and relative humidity levels inside a building with no heating, ventilating, and air condition system (HVAC), fluctuate widely with the heating of the day and then cooling of night. Objects made of organic materials such as paper, wood, leather, textiles, etc. swell and contract according to the temperature and humidity levels, and can suffer irreversible damage when subjected to such fluctuation. They may warp, become brittle, tear, break, split, grow mold – any number of things. Choose a storage area that is the least prone to temperature fluctuations such as an interior closet or windowless room; avoid basements, attics, and un-insulated areas of the building.

Air Pollutants

There are two types of air pollutants – particulate and gaseous. Both can damage historical collections. Particulate contaminates such as dust, soot, and pollen can soil, chafe or otherwise blemish artifacts. Gaseous pollutants such as ozone, peroxides, nitrogen oxide, and sulfur dioxides can react chemically with other materials to form acid which can harm artifacts. The acid can form within the artifact itself or it can migrate from one material to another. Avoid storing or exhibiting artifacts near fireplaces, cooking places or smoking areas. Keeping all windows and doors closed tightly will also ensure a reduction in pollutants. General housekeeping, such as cleaning the floors, walls, windows, storage shelves, light fixtures, and office equipment is essential to reducing the air pollutants in the storage area. Use only mild cleansers and avoid harsh commercial cleaners that contain ingredients such as bleach or ammonia.

Pests

The three categories of pests are: microorganisms, such as mold and mildew; insects, such as moths, beetles, and silverfish; and vertebrates, such as birds and mammals. The best defense is a combination of prevention and constant vigilance. Also, discourage pest activity by eliminating food, beverages, potted plants, and dried and fresh flowers from object storage, work, and display areas. Outside the building, avoid plants and flowers that attract insects. A dust-free museum environment will also reduce insect activity, so good housekeeping is a must. Regular monitoring for pests can help detect their presence before a major infestation occurs. Place sticky traps strategically throughout the building to monitor what kinds of pests are getting in and in what numbers. Periodically inspect artifacts on display and in storage for evidence of insect activity – eggs, larvae, powdery deposits or small holes. During inspections, look for signs of mold or mildew. Any contaminated artifact should be placed in isolation immediately.

Storage of Collections

In addition to a proper environment, storage units – cabinets or shelves – are also important. Museum specific storage units are the preferred option, but can be costly. The next best option is sturdy steel shelving or cabinets. Look for ones that have a synthetic polymer powder coating. Anodized aluminum is another good option. Wood shelving can be problematic because wood emits harmful acids and other substances. Oak is the most volatile. If wood is the only option available, make sure it is properly sealed with a quality water-based polyurethane or paint. It must still be lined with some sort of barrier, such as acid-free paper or barrier board. Note: Properly prepared wood storage units are best for audio and audio-visual collections.

Artifact collections also need to be stored in suitable containers. Choose archival-safe, chemically stable materials such as acid-free cardboard boxes, tissue, foam, folders, and hangers that are the appropriate size and type for each artifact. Ideally, only one artifact should be stored in each container. These containers will protect the artifacts from light, dust, harmful pollutants, and pests. Avoid plastic containers. as they don’t allow circulation of air. In the event that items get wet, mold and fungus can grow if entirely enclosed in plastic. Consult the resource page for a listing of vendors that specialize in archival containers.

Storage location is also an important factor in preservation. Avoid storing artifacts along exterior walls since temperature and relative humidity levels fluctuate more readily there. Also avoid storing an artifact on the ground. All artifacts should be placed at least 12 inches from the floor to protect against flooding. Similarly, never store artifacts near or below windows, water pipes, water heaters, or HVAC units and vents. Artifacts in storage should be inspected periodically to assess their condition. Check for any signs of deterioration and for evidence of pest activity. These inspections should be documented and saved as part of the museum’s records.

Display of Objects

While an artifact may spend much of its life in storage, it will likely spend some time on display as well. To ensure the long-term preservation of the object, certain measures need to be taken while it is on display.

Again, maintain the proper environment as described in the above sections. Controls for light, temperature, relative humidity, air pollutants, and pests should be in place throughout the display area. If artifacts are displayed inside cases, make sure that the environment inside the case is as ideal as possible. Heat and moisture can easily get trapped inside the cases, so diligent observation of conditions is required. Exhibit cases and mounting materials should be made of inert materials, especially those in direct contact with an artifact.

Wood cases can be altered to make them acceptable for displaying historic artifacts by sealing the surfaces with a quality, water-based polyurethane. Then the cases must be allowed to air out for at least three to four weeks. At the very least, place a barrier between the artifact and the wood surface. Appropriate barrier materials include Mylar, Melinex, or acid-free buffered paper, tissue or barrier board. If surfaces require padding, consider polyester batting, polyethylene foam, or unbleached, undyed cotton muslin.

As a general rule, do not use adhesives or sticky substances of any kind to mount or aid in the display of any artifact (including photographs). Original clamps, hooks, strings, straps, or handles already attached to an artifact should not be used for support or to take the weight of that artifact. The display technique should place the least amount of stress on an artifact as possible.

Be mindful of the location of artifacts on display. Avoid displays near windows and doors where temperature and light levels can be problematic. Placing artifacts near air conditioning or heating vents should also be avoided. Be careful to not place artifacts or cases in such locations that they will be easily bumped or knocked over.

Record Keeping and Documentation

Providing adequate care for the long-term preservation of artifact collections also requires the lodge keep accurate and thorough records on every artifact in its possession. Records should be considered an important part of the object itself.

>A simple Excel spreadsheet is adequate for maintaining the following basic artifact information:

Include a notes field in addition to the above to document any significant historical information on the object that may give context and meaning to why the object was chosen for preservation. You may need to document framed items in various rooms as well as any significant furniture or regalia the Lodge may own. Print a copy of the artifact spreadsheet in case of loss of the digital original. At least one paper copy and one digital copy should be kept locked in a fireproof cabinet on the museum’s premises, while another copy should be secured off-site.

PHOTO CREDIT: Paolo Vescia

Junior Grand Warden Arthur H. Weiss explains the beauty and significance of Masonic material culture.

Material objects convey culture and reflect shared experiences that span time and geography. Few organizations have as rich a material culture as Freemasonry. Brothers’ lodge attire, jewelry, Masonic gifts, lodge rooms, and ceremonial tools have a profound effect on the member experience – and they do so by design.