Leading With Beauty

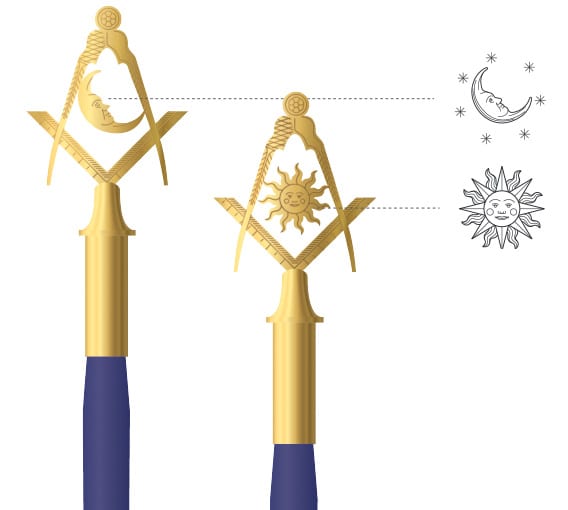

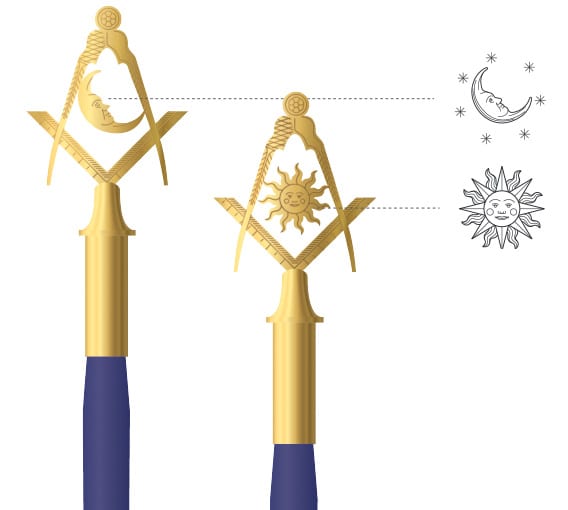

The Masonic rods that deacons and stewards use within the ceremonial lodge are imbued with meaning and symbolism.

By Drea Muldavin-Roemer

Every object has a story to tell. Who made it? What was it used for? What does it symbolize? Such are the questions posed by the collection of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry, which holds the archives of the Grand Lodge of California. From diaries to jewels to aprons, these artifacts tell the story of California through the lens of Masonry over the past two centuries.

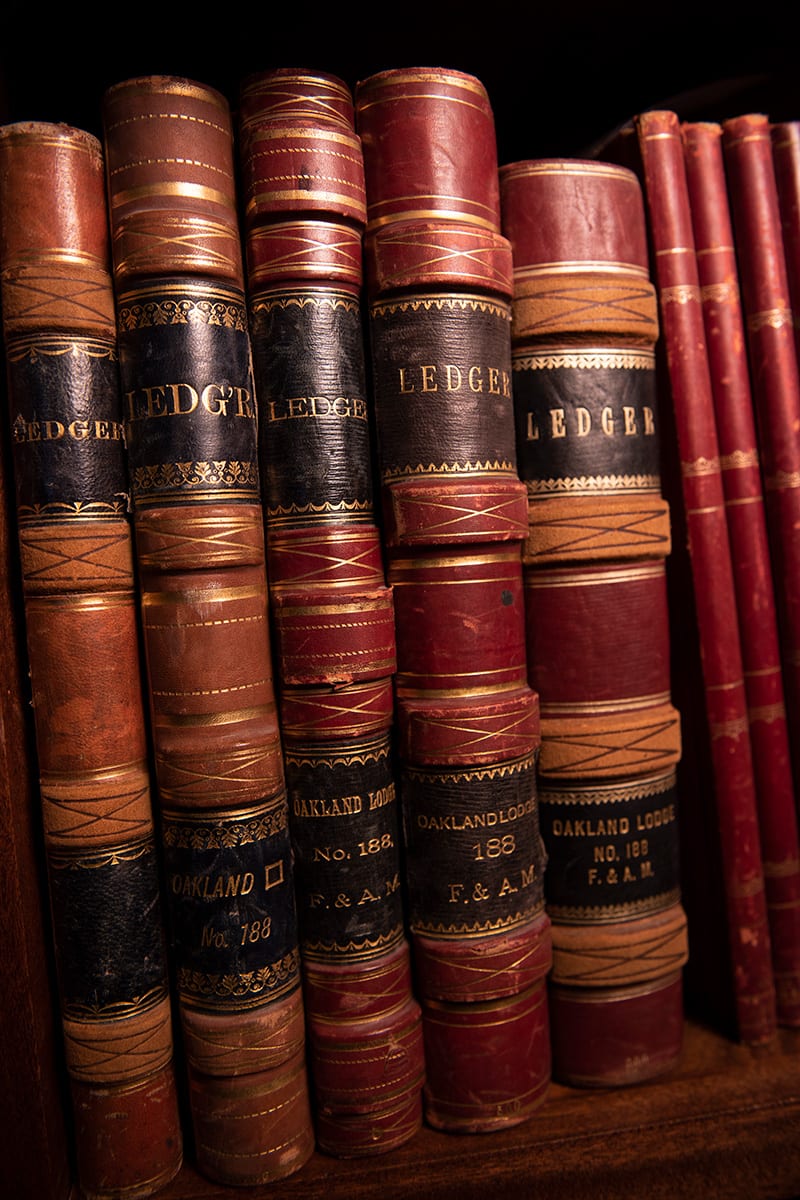

The Grand Lodge’s collection was started by California’s first Masons in the 19th century. Unfortunately, many historic materials – including detailed membership records – were destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906. In the years since, the collection has been rebuilt, primarily through donations by members and their relatives. Today, its location inside the California Masonic Memorial Temple in San Francisco contains around 800 aprons; ritual objects and jewelry; a rare book collection, including first editions of early Masonic texts; a large bible collection (the oldest dating back to 1599); a significant collection of sheet music and songbooks; and even an organ. It also houses an extensive archival component, containing manuscripts, letters, ledger books, and even diaries.

“Within these documents is the history of a community,” says Collections Manager Joseph Evans. “As a total body of work, this material reveals the stories that make up Freemasonry throughout the state.”

One such story is that of United States Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, who spearheaded some of this country’s most historic decisions – including Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which ruled racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. In 1935, before serving as California’s governor and on the Supreme Court, Warren was grand master of Masons in California. The museum’s collection includes some of his correspondence, datebooks, and other writings. It also houses personal items from such famous Californians as Charles Crocker and Leland Stanford – two of the “Big Four” railroad giants. As Evans points out, almost all prominent early Californians were also Freemasons.

One such story is that of United States Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, who spearheaded some of this country’s most historic decisions – including Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which ruled racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. In 1935, before serving as California’s governor and on the Supreme Court, Warren was grand master of Masons in California. The museum’s collection includes some of his correspondence, datebooks, and other writings. It also houses personal items from such famous Californians as Charles Crocker and Leland Stanford – two of the “Big Four” railroad giants. As Evans points out, almost all prominent early Californians were also Freemasons.

The collection stretches beyond California, too. This is especially true of its Masonic aprons, many of which originated in France, England, Scotland, and throughout the United States. Some date back to the mid-1700s, and one belonged to famed explorer Davy Crockett, circa 1820. The museum’s regalia collection includes swords and capes from Knights Templar commanderies and Shriner fezzes, as well as trowels, pitchers, cups, and utensils embossed with Masonic symbols.

Since its founding, the HWC Library and Museum’s main focus has been to provide information about the fraternity. “It began as a means of educating the brotherhood,” says Evans. “Before the museum was established, it was difficult for members to access Masonic materials. They aren’t something brothers can access in a public library and many Masonic texts weren’t affordable.”

For many years, Masons ran the library and museum on a volunteer basis. Through the dedication of these brothers, and former collections manager Adam Kendall, its impressive collections have continued to expand. Today, Evans is working to elevate the knowledge all members can gain from the collection by initiating a new internship program. He is partnering with the University of San Francisco and San Francisco State University to bring museum studies graduate students to the library and museum to help catalogue and preserve its contents. While learning more about Freemasonry and the archives, they will bring fresh perspectives and emerging best practices to the collections, helping Evans find new ways to share the stories of Freemasonry in California with the wider community.

When asked how the museum’s collection symbolizes the Masonic ethos of love and unity, Evans points to a powder horn from 1827, carved with Masonic symbols and the words, “Cemented with love.”

“You can tell that this man spent a lot of time on this piece,” Evans says. “It really conveys his emotions around Freemasonry, including the sense of connection and community that he found within the fraternity. I see that throughout the collection. The objects that truly symbolize love and fraternalism are the ones that meant the most to Masons and their loved ones – and they are the objects that endure.”

“You can tell that this man spent a lot of time on this piece,” Evans says. “It really conveys his emotions around Freemasonry, including the sense of connection and community that he found within the fraternity. I see that throughout the collection. The objects that truly symbolize love and fraternalism are the ones that meant the most to Masons and their loved ones – and they are the objects that endure.”

The museum’s collections are a palpable reminder of the importance of ritual in the Masonic tradition. They convey the fraternity’s unique ability to bring people together in fellowship and mutual respect. Adorned with the words and symbols of Masonic teachings, these objects provide a tangible connection between all Freemasons, across time and place, reminding those who encounter them that the past and present are deeply intertwined. Much like Freemasonry itself, these pieces of history have stood the test of time, and are a testament to the enduring nature of Masonic brotherhood.

The Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum collection is available to researchers by appointment, Monday through Friday, at the California Masonic Memorial Temple in San Francisco. To schedule an appointment, email jevans@freemason.org.

Explore the archives online at masonicheritage.org

The Masonic rods that deacons and stewards use within the ceremonial lodge are imbued with meaning and symbolism.

Freemasonry’s material culture holds deep meaning for its members – and the same can be said for organizations throughout the world. Here, we look at examples of material culture within the fraternity and the wider world that convey emotional and experiential significance.

Lodges accumulate a mountain of records over the years, in the form of papers, books, artifacts, and photos. The sheer volume can get overwhelming.

Use these guidelines and tools to get rid of the clutter, and to take proper care of your lodge’s important records.